Beyond “Happy Holidays!”: it’s time to support Canada’s increasing religious diversity

“Happy holidays!” Canadians use this greeting to be inclusive of all religious celebrations that take place this month. But there aren’t actually many religious holidays in December, and only Christmas aligns with our statutory break. So how inclusive is Canada of religious diversity?

Canada’s religious demographics have changed in the last 20 years. The 2021 census shows that Canada is becoming less Christian overall, with both religious diversity and secularism on the rise. This is particularly true in British Columbia where we have one of the largest proportions of both secularism and non-Christian religious faith.

92.0% of the population aged 15 and older agreed that ethnic or cultural diversity is a Canadian value. (StatsCan, 2022)

As immigration is the primary driver of ethnocultural and religious diversity and work is the primary driver of immigration, it is important that we move beyond symbolic gestures of equity and provide structural support for the religious freedoms of those who come here to live and work.

Christianity is in decline, religious diversity and secularism are on the rise

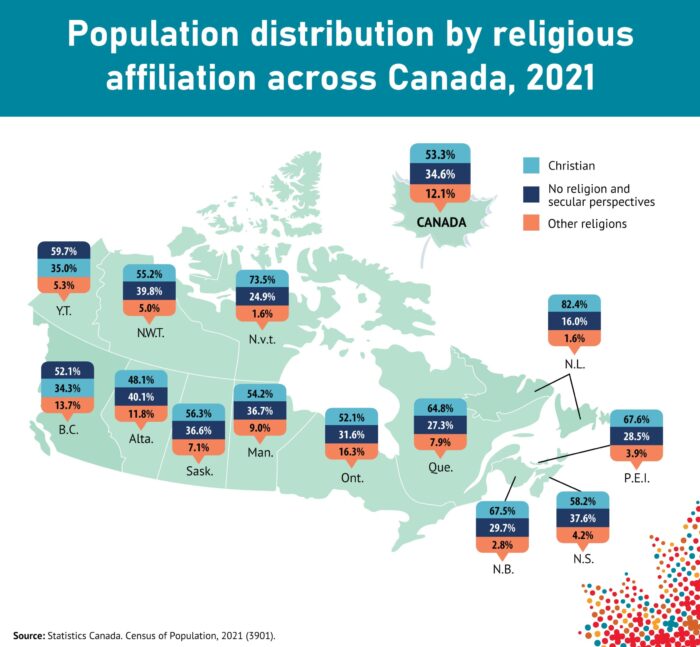

While Christianity remains the most prevalent religion in Canada, its share of the population has been steadily decreasing over the past 20 years. In 2021, 19.3 million people, or just over half (53.3%) of the Canadian population, identified as Christian—a notable decrease from its 77.1% share in 2001.

On the other hand, the 2021 census shows that the proportion of the population reporting affiliations with non-Christian religions, such as Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism, has seen a substantial increase.1 The share of the Muslim population in Canada has more than doubled in the last 20 years, increasing from 2.0% in 2001 to 4.9% in 2021, making Islam “the second most commonly reported religion in Canada, with nearly 1.8 million, or 1 in 20, people.” Canada is also now home to close to 830,000 Hindus and approximately 770,000 Sikhs, the highest proportion of whom live in BC.

At the same time, there has been a decline in religious affiliation overall, with more than a third of Canada’s population (34.6%) reporting no religious affiliation (compared with only 16.5% of the population in 2001).

These trends are particularly pronounced here in BC. The province has the smallest proportion of Christians (34.3%), the second largest proportion of secularism (52.1%), and the second largest proportion of non-Christian religious affiliations (13.7%).

Immigration is the driver of religious diversity, work is the driver

of immigration

Immigration is a key driver of ethnocultural and religious diversity in BC and in Canada more broadly. Immigrants make up about a quarter of the population (23%) in Canada but make up the majority of Buddhists (68.9%), Muslims (63.1%), Hindus (62.9%), and Sikhs (53.8%). Immigrants are far more racialized (69.3%) than their Canadian-born counterparts (11.4%) and this diversity is increasing; over the last five years, the proportion of new immigrants who are racialized is higher than ever (83%).

A large share of recent immigrants were selected for their ability to contribute to Canada’s economy” (StatsCan, 2022)

Canada’s immigration policy is largely designed to accommodate employers’ demands for cheap labour. More than half of immigrants that have been admitted to Canada in the last five years have been admitted under the economic category and immigrants have accounted for 80% of the labour force growth in the same period. These numbers don’t include the more than 777,000 temporary foreign workers or the 354,000 international students working in Canada. Immigration and temporary migration certainly help employers circumvent the growing demands for better wages, but what are we doing to meet the needs of these undervalued workers?

The intersection of immigration, work, race, and religious diversity is a critical area of focus for policy change

The significant growth rate of BC’s population is fueled by immigration, especially in the Lower Mainland, which hosts a substantial and rapidly expanding immigrant community. Immigrants make up 31.4% of the labour force in the province, not counting the more than 30,000 workers on temporary permits.

But immigrants and non-permanent residents in BC, particularly those from racialized groups, face a compounded intersection of discrimination, insecurity and poverty. They are more likely to experience discrimination, often work in jobs that do not utilize their skills, earn less than their white counterparts, have higher rates of poverty and are more likely to be in core housing need. This precarity is even more pronounced for the increasing number of workers in Canada without permanent status.

These challenges highlight the need for provincial policies that better support immigrants and promote inclusivity and equity, particularly in their working lives.

The secular workplace should work for everyone

The Canadian state follows an open model of secularism with the fundamental objective of religious freedom and equality. However, work in Canada is largely structured around Christian traditions and practices. The Monday to Friday work week aligns with the Judeo-Christian Sabbath and statutory holidays such as Christmas and Easter are based on Christian observances. These structures can inadvertently exclude or disadvantage those of non-Christian faiths whose religious observances and practices may not align with the standard work schedule or recognized holidays.

For the more than 125,000 Muslims in BC, for example, Friday is the day of prayer (“Jumu’ah”), accommodations for Ramadan are rare, and no statutory holidays align with either Eid al-Fitr or Eid al-Adha, Islam’s most important religious holidays. Besides the tension these gaps can cause between work, home and faith, the ideological impact of such exclusion from the socioeconomic life of the province can rob us of the promises of cultural diversity.

The BC Human Rights Code offers some protections for workers to seek accommodations from their employers for their religious beliefs, observances and practices. However, inequity in the labour market and in society more broadly impacts racialized immigrant and migrant workers’ ability to exercise this right.

The path forward for happy holidays

Socio-economic equity strengthens religious freedom. A core focus of our work at the CCPA–BC is developing research-backed policy alternatives that tackle multiple dimensions of inequity and precarity in BC. This year, we recommended policies to address income inequality, wealth redistribution, affordability, the housing crisis and precarious employment, including the unjust and racist labour policies that govern migrant farmwork and platform work. Taken together, our policy recommendations would reduce the precarity faced by racialized immigrant workers and strengthen their agency at work.

If the BC government commits to addressing these systemic issues impacting far too many families in the province, then we truly could have “happy holidays” for all.

1 The number of people who reported Jewish or Buddhist religious affiliation has not changed significantly over the past 20 years, representing approximately 1% of the population respectively. (Click here to resume reading)

Topics: Economy, Employment & labour, Immigrants & refugees, Racism & racial justice