Urgent action needed to control rent increases: Submission to the BC Rental Housing Task Force

On July 3rd, we shared our recommendations regarding BC’s Residential Tenancy Act and controlling rental costs in British Columbia with the BC Rental Housing Task Force. This is our submission.

As we noted in our March submission to the BC government’s poverty reduction consultation, we believe that bold action to control rental costs must be a central component of a comprehensive and effective poverty reduction plan. We wrote then:

While the government has begun to take needed action to cool the housing market and build new low-income housing, more is urgently needed to control rent increases.

This issue arguably represents the greatest threat not only to the poverty reduction plan, but to the government’s overall policy agenda. Given escalating housing costs, there is a grave risk that all the improvements and gains experienced for low-income people due to minimum wage increases, welfare rate increases, child care fee reductions and more will be wiped out by rent increases.

The government was quick to end the fixed-term lease loophole last fall. But other reforms are urgently needed to the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA). Currently, the RTA only limits rent increases for existing tenants. Once a tenant moves or is evicted, landlords are free to increase the rent as they wish. Moreover, even when rent control is in place, the current RTA allowance of annual increases of CPI plus 2%, compounded, means rents have been far out-stripping inflation in recent years.

Given this, we strongly recommend, as does the BC Poverty Reduction Coalition, that the provincial government introduce stronger tenant protections including tighter limits on annual rent increases, tying rent control to the unit (not the tenant), and strengthening the application and enforcement of the Residential Tenancy Act.

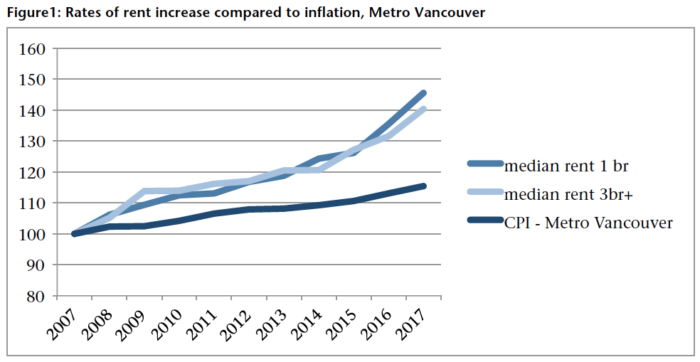

Rent increases far outstripping inflation

Evidence for BC’s escalating rents can be seen in the annual Living Wage for Families calculation. We at the CCPA-BC developed the methodology for calculating the living wage for families, and each year since 2008 (when we published the first living wage report) we have updated the calculation for Metro Vancouver.1 Not surprisingly, rent is the single most expensive item in the model living wage family’s budget. Particularly troubling, however, is the trend for rental costs (based on median rent for a 3-bedroom unit2) to consistently increase by considerably more than the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rate.

Between 2007 and 2017, the cost of rent for the Metro Vancouver living wage family increased by 40.4%, whereas the CPI inflation rate for Metro Vancouver during that same period was only 15.5%.

More broadly, the cost of a rental apartment has risen more than twice the rate of inflation in the last decade. For example, the median cost of a bachelor apartment in Metro Vancouver went from $738 in 2007 to $1,010 in 2017, an increase of 36.9%3 compared to Vancouver’s CPI increase of 15.5%. The increases in median rent for one- and two-bedroom apartments in Metro Vancouver have been similarly high (45.6% and 43.9%). Although rental costs are lower outside Metro Vancouver, rent increases across BC have been similarly high. The median rental costs have risen much faster than inflation across BC, with some communities like Nanaimo seeing median rents nearly double over the last decade.4

Source: CMHC Rental Market Survey (rents) and Statistics Canada (annual CPI). Note that rents reflect primary rental market only.

As seen in this year’s living wage update, the hourly wage needed to cover the cost of raising a family in Metro Vancouver increased modestly from $20.62/hour in 2017 to $20.91/hour in 2018. This is the hourly wage that two working parents with two young children must each earn to meet their basic expenses (including rent, child care, food and transportation), once government taxes, credits, deductions and subsidies have been taken into account. Notably, despite modelling the first 50% cut to MSP premiums and the first round of reductions to child care fees (thanks to recent BC government policies), the living wage still increased due to a 7% increase in rent. This reality captures the stress facing so many families as they wrestle with the housing crisis. But it also highlights the profound risk facing the government’s policy agenda, namely, that if left unchecked, rent increases will swallow up all the gains from the government’s other policy initiatives.

The need for stronger rent control

Given the above, we strongly concur with the central recommendation you have heard from the Vancouver Tenants Union, the BC Poverty Reduction Coalition, and no doubt many others, namely, that the rent control provisions in BC’s RTA be updated to limit rent increases to once every 12 months regardless of whether there has been a change of tenant. This is vital to discourage evictions.

Additionally, it is our view that allowing annual increases of 2% beyond inflation is excessive and, compounded over many years, it is exacerbating the problem of escalating rents.

If a landlord pays for significant repairs or improvements, or experiences other cost increases beyond inflation, such that they believe they should be allowed to increase monthly rent beyond the statutory limit, they should have to make a special application to the Residential Tenancy Branch (RTB), documenting their expenses. These costs (after accounting for tax deductions) should be amortized over an extended period of years so that rent increases remain modest and even these increases should be capped.

Enforcement and fines for fraudulent evictions

The RTB needs additional resources to enforce the RTA, and tougher rules are needed to ensure that people are not fraudulently evicted based on spurious claims that the unit is to be used for family members. We concur with the Vancouver Tenants Union recommendations in this regard.5

Expand the regulation of Airbnb and other temporary rental platforms

A key piece of controlling rents is increasing the rental stock and boosting vacancy rates, and an important element to achieve this goal is to return to the rental market apartments that are sitting empty or being used for temporary rentals. Given this, we applaud the new government’s speculation tax as an effort to shift empty housing into the rental market. We also believe that the regulations that have been put in place by the City of Vancouver to limit the use of Airbnb are very well advised and well designed. The Province should consider expanding such regulations to all regions with a low vacancy rate.

Would tighter rent control discourage construction of new rental stock?

We do not believe so.

We do indeed need a substantial build-out of affordable rental housing. Ultimately, a key means of stabilizing rents is a relatively high vacancy rate — a higher vacancy rate is a renter’s friend. This in turn requires more affordable rental stock.

That does not mean, however, that the rental regulatory regime must be structured to win the favour of the private development industry. The government can and should establish stronger renter protections and should feel empowered to more effectively use zoning powers to direct the kind of housing to be built. Fundamentally, the government itself will have to do more of the heavy lifting when it comes to directly building new affordable rental stock.

We believe warnings that tighter rent controls will discourage new rental construction to be overstated for the following reasons:

- First, it will be possible to charge market rents for new rental stock (subject only to limitations stemming from agreements and partnerships with the Province and municipal governments whereby some new stock is designated for below-market rental units in exchange for public land or density bonuses or as part of a larger development permit). The current reality of high market rents should mean that private developers have plenty of incentive to build new stock.

- Second, construction of new rental stock is likely more influenced by zoning rules than by factors such as rent control. If large areas are targeted for up-zoning, with the proviso that new density must be for rental housing, then that is what the private development industry will build. The market will build what and where it is permitted. Governments have the regulatory and zoning power to shift the dominant form of market production from expensive condos to more affordable rental. The recent law from the new provincial government allowing municipalities to zone certain areas for rental-only housing is a helpful step and hopefully one municipal governments will feel pressured to take full advantage of.

- Third, of course, we need the provincial government itself to drive construction of new affordable rental housing. The new government has taken some important steps in this direction with its first budget, but more is needed, and—thus far—too much reliance has been placed on the private sector to meet the government’s 10-year housing target of 114,000 new units. The government can and should see the construction of new rental units as an investment, the costs of which will be recouped over time in rental income. While the BC government is currently planning to build about 30,000 new units of affordable housing over 10 years, the CCPA-BC has recommended a more ambitious build-out of 5–10,000 units per year of social and co-op housing in Metro Vancouver alone.6 Ultimately, the government must commit to its target of 114,000 new units (and likely more), and if private partners prove unwilling to help fully meet that goal, then the government must meet the goal on its own.

A higher vacancy rate is a renter’s friend.

A 2011 study from the University of Winnipeg’s Department of Economics finds that Manitoba’s strong rent control regime has had no negative effect on the rental market.7 In Manitoba (unlike in BC), rent control is tied to the unit (not the tenant), as we propose above, but “Landlords may apply for an increase above the guideline [regulatory cap] based upon a review of their operating costs, capital expenditures and any financial loss experienced.”8 The study found that rent controls had no harmful impact on the rate of new rental construction or on the quality of the rental stock. This study is well worth close examination by this Task Force.9

Given the above, it is important that the provincial government not shy away from tightening rent controls out of fear that private construction of new rental stock will be discouraged.

Rental credit

Rental credits or subsidies without stronger rent controls provide little help because in a tight rental market, increased government assistance to renters risks merely being passed on to landlords in higher rents. However, provided stronger rent control is in place (as outlined above), new rental credits or subsidies can offer meaningful help to struggling low and modest-income households.

The CCPA has previously proposed that the Province reformulate the $800 million-per-year Home Owner Grant (HOG) into a housing credit that would go to owner and renter households alike and be linked to income. In this way, the credit could focus on low and modest-income households that actually need assistance, and would not go to upper-income homeowners or renters who don’t (unlike the current HOG, which benefits all home owners of properties under a certain market value threshold regardless of their income level). Such a new housing credit would be refundable and would phase out gradually as household income rises (as is the case for Old Age Security or the Canada Child Benefit). This new housing credit would increase fairness between renters and owners, and would be more consistent with the government’s promise to bring in a “renters’ rebate.”

Another more ambitious approach well worth consideration would be for BC to follow the lead of Manitoba’s Rent Assist Program. Established in 2015 by Manitoba’s previous NDP provincial government, but with all-party support, this program provides a rental income support transfer to all lower-income Manitobans who pay rent of 75% of the median market rent or less. As the Caledon Institute notes in their recent report about this program:

“Rent Assist is unique in making housing affordable for almost every resident of the province… Manitoba’s Rent Assist housing allowance is designed so that renters in the private market pay no more than 28 percent of their income on housing, if they are renting a modestly-priced apartment (defined as 75 percent of median market rent). Rent Assist offers the same financial benefit to everyone with low incomes in private market rental housing, whether on social assistance or not.” 10

The credit could focus on low- and modest-income households that actually need assistance.

Were BC to institute an income-tested program such as this, it would supplant the shelter support component of social assistance (removing this expenditure from the welfare budget entirely), as well as the Province’s existing rental subsidy programs—the Rental Assistance Program and the SAFER program for seniors. It would much more cleanly provide housing support to all lower-income renters regardless of their age, family composition or source of income. This could be a great boost to poverty reduction, provided, as mentioned above, that it is accompanied by stronger rent controls. Indeed, because this program is linked to the median market rent, it prevents inflation from eroding the real value of the benefit to renters and creates an incentive for the government to further control rental costs. The benefit amount is based on family income and size, not on actual rent (which simplifies program delivery), and is portable as people move between apartments, and as they move from social assistance to the labour market.11

In conclusion, we note the importance of the ideas above being understood as a package—rent control, an ambitious build-out of new affordable stock, and enhanced rental credits/subsidies cannot be seen as different options for controlling rental housing costs. Rather, the effectiveness of each measure depends on the others. Taken as a whole, such policies would serve to moderate rental housing costs and restore affordability.

We hope these policy ideas and recommendations prove useful to your deliberations. Thank you again for your consideration of our views on this important subject.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Marc Lee and Alex Hemingway for reviewing a draft of this submission. The opinions are those of the authors. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Vancouver Foundation for the poverty reduction work we are currently engaged in.

Notes

- For more on the Living Wage for Families, including the latest annual update and the original 2008 report, see: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/livingwage2018

- For the living wage calculation, we use median rent of purpose-built rental units with 3 or more bedrooms in Metro Vancouver. Note that rents in purpose-built rental units tend to be lower on average than rents in the secondary rental market (all other rentals). Data from CMHC’s Rental Market Survey. Available at CMHC’s Housing Market Information Portal: https://www03.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/hmiportal/en/#Profile/1/1/Canada

- All rent statistics in this Submission are based on data from the purpose-built rental market only. Data from CMHC’s Rental Market Survey.

- The only notable exception to this trend is Fort St John where the median rent increase has kept pace with inflation and median rent for one bedroom units has fallen since the boom of 2007.

- All the VTU recommendations can be found at: https://www.vancouvertenantsunion.ca/recommendations_to_the_bc_rental_task_force

- For more on the CCPA-BC housing ideas, see our 2016 report by Marc Lee, available here: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/getting-serious-about-affordable-housing-towards-plan-metro-vancouver

- Grant, Hugh. 2011. “An Analysis of Manitoba’s Rent Regulation Program and the Impact on the Rental Housing Market” http://www.gov.mb.ca/cca/pubs/rental_report.pdf

- Ibid.

- Manitoba’s annual allowable increase is based on CPI alone (they do not allow 2% beyond inflation, as BC currently does). The Manitoba rent controls do have some exemptions, which you can find here: http://www.gov.mb.ca/cca/rtb/rentincreaseguideline/currentrentguideline.html

- Brandon, Josh, Jesse Hajer and Michael Mendelson. 2017. “What does an actual housing allowance look like? Manitoba’s Rent Assist program.” Toronto: Caledon Institute of Social Policy. https://maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/1117ENG.pdf

- The CCPA-Manitoba has also published on Manitoba’s Rent Assist program, available here: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/commentary/fast-facts-rent-assist-increase

Topics: Housing & homelessness, Poverty, inequality & welfare