Time to Rethink The Way We Fund Higher Education

This September, like every year, a new group of high school graduates headed to college or university to pursue higher education. But today’s generation of students is in for a very different experience from the ones their parents had.

On campuses across the country shiny new buildings are popping up, bearing corporate logos or the names of local philanthropists. But most of these are reserved for graduate schools of business, law or medicine, so today’s undergraduate arts and science students can expect to find their classes in the older buildings, often in varying states of disrepair. There, students will be crammed into large classes, often with hundreds of others, and are much more likely to be taught by underpaid sessional instructors on contract rather than tenured professors. And all that despite paying considerably higher tuition fees than their parents’ generation.

Higher education in Canada is being transformed, and not in a good way, as colleges and universities scramble to replace the public funding they used to rely on with tuition fees and private donations. Government funding has not kept pace with the increasing costs of education, falling from 84% to 58% of university operating budgets over the last 30 years. Colleges have also seen a significant decline, from 88% to 74%.

This has given rise to a number of worrisome trends. For students, it means increased financial barriers to education as tuition fees more than doubled since the early 1990s, and that’s after adjusting for inflation. It is no longer possible to earn enough in a summer job to pay for tuition (let alone living expenses). While financial aid spending has increased, much of the support is now provided through loans rather than grants. It’s hardly surprising, then, that student debt ballooned over a generation, doubling in real terms over the 1990s and growing more moderately, but still faster than inflation, over the 2000s. Even if those moderate trends persist over the 2010s – and there’s no guarantee they will – today’s university students who borrow to pay for their degree (58% of all students in 2009) are looking at an average debt load of $34,000 upon graduation in 2016. College students will rack up half of that amount as they typically enroll in shorter programs with lower tuition fees. Students pursuing graduate programs will often borrow a lot more.

This is fundamentally inequitable, because it means that the lower income students who are more likely to take out loans end up paying considerably more for the same education (through interest on their debt) than their peers whose parents can afford the tuition fees up front. There is increasing evidence that high debt levels are an obstacle for many of the highest-needs students as they transition into the workforce and start families.

For colleges and universities, increased reliance on corporate donations and philanthropy means that fundraising consumes a growing share of resources that could instead be dedicated to teaching and research. It has also shifted how universities spend their money: there’s less of a focus on teaching and a shift towards research, which is easier to fund privately. This has negatively affected the undergraduate educational experience. In addition, the increasing share of university research budgets coming from corporate sources and the growing number of law and public policy schools underwritten by big business is starting to raise questions about the independence of university research and more fundamentally, about the changing nature of what research does and does not get done.

Policy-makers have largely ignored these trends so far, but it’s time to rethink how we fund colleges and universities before we reach a crisis point. The reality is that if we want our institutions of higher learning to provide a top-notch educational experience, to be accessible to all Canadians regardless of their family finances, and to produce independent research that furthers the public interest (rather than being driven by private funders’ agendas), we must increase government funding for higher education.

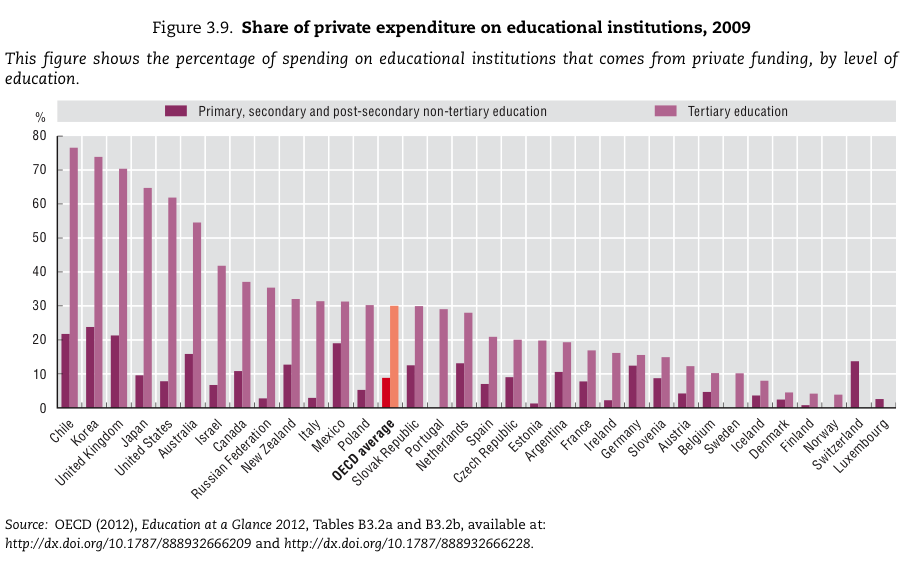

This is not a pipe dream – it’s how education is financed in most of the other developed countries. Canada is among the OECD countries with the highest reliance on private funding for higher education. Only Chile, Korea, Japan, the US, the UK, Australia and Israel provide less public support for higher education out of 32 developed countries. Many countries in Europe fund over 80% of higher education through the public purse.

An educated and highly skilled workforce is crucial for success in the modern economy and is associated with a number of social benefits, such as better health, increased civic engagement and stronger democracy. It is estimated that over the next decade, more than three quarters of new jobs will require some form of post-secondary education. Currently, just over half of working-age Canadians have a degree or certificate above a high school diploma. While education levels are higher for younger Canadians, only 67% of those aged 25-34 have completed some form of post-secondary education.

It seems clear that we are not producing the graduates we need to meet the demands of our changing and aging workforce. Canada’s proposed solution – to import the workers needed – is short-sighted. What we need is an expansion of our higher education participation rates, not of the temporary foreign worker program.

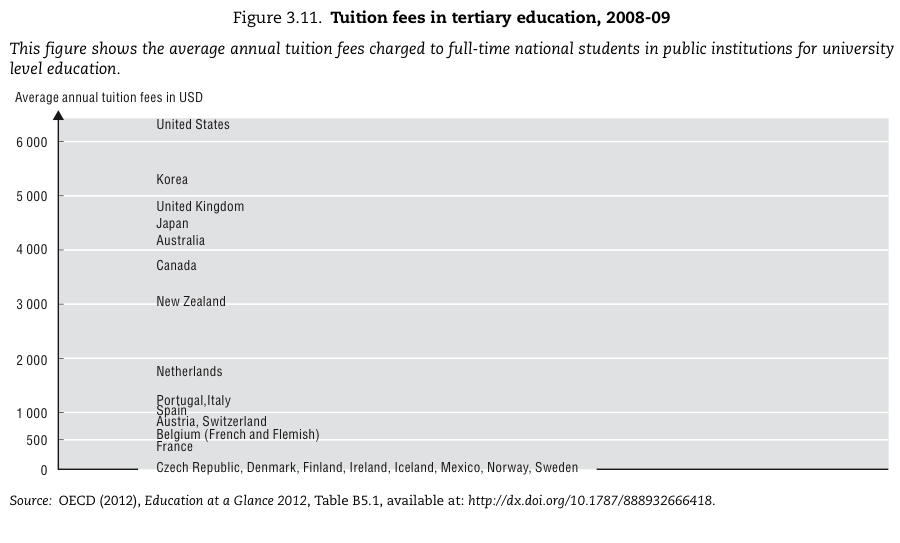

And as higher education increasingly becomes a standard job requirement, it’s time to consider expanding publicly provided education beyond secondary schools and into institutions of higher learning. Many other countries have done this. OECD’s latest Education at a Glance report shows that out of 25 countries that provide data on tuition fees, two-thirds either charge no tuition at all or only charge nominal fees (lower than $1,200 US per year).

Of course, funding higher education through the public purse doesn’t make it free. We still pay for it, just like we pay for roads, hospitals and clean drinking water – through our taxes. But if you think about it, funding higher education through progressive taxation is a much fairer way to do it than charging students upfront. It doesn’t mean that graduates get a free ride – they will still pay for their degrees, but they do so at a time when they are better positioned to afford it – after they’ve started working and are reaping the benefits of their education.

—-

A shorter version of this piece ran online at WISE – World Innovation Summit for Education.

Topics: Children & youth, Economy, Education, Employment & labour, Provincial budget & finance, Taxes