Vancouver’s Secured Rental Policy and the battle over density

In North American cities with growing populations and economies, a similar political story on housing affordability is playing out. Calls to permit more dense housing supply—also known as upzoning or changes to land use regulations to allow multi-unit buildings on “single-family” detached lots—pit older, wealthier homeowners against younger, less affluent, renters who feel shut out from most of the city. New development also raises concerns about displacement of low- and moderate-income people living in existing affordable rental housing stock.

The City of Vancouver’s Secured Rental Policy (SRP), passed by council in November 2019, aims to strike a balance between these positions with the objective of incentivizing the development of market rental housing on and close to main streets. Much of the policy is in the form of a two-year pilot program, but the new policy also sets the stage for upzoning as part of a more comprehensive city-wide planning exercise. The pilot will also have implications for similar moves in other Metro Vancouver municipalities.

The case for density

Over the past three decades, most of Vancouver’s higher-density housing has been built on former industrial land and at major transit hubs and arterial roads. Low-density neighbourhoods, where local opposition poses a political challenge that must be overcome, have been left largely untouched. Former Vancouver City councillor Gordon Price calls this the Grand Bargain: “high-rise density, low-scale suburbia, little in between. Massive change for one, almost none for the other, and spot rezonings thereafter.”

Due to the vexing issue of housing affordability, the call for new higher-density supply is coming to those low-density neighbourhoods. In the City of Vancouver “gentle density” increases over the past couple of decades—legalization of secondary suites, allowing laneway houses and, more recently, a trial period allowing duplexes—have already been implemented in these low-density neighbourhoods, with secondary suites in particular a major source of affordable rental housing supply.

Further steps down this path could look like Portland, Oregon, which recently made a splash with its new Residential Infill Project (RIP), which allows development of tri and fourplexes on single-family detached lots city-wide. A “deeper affordability bonus” allows up to six units if half or more of new units are regulated and affordable, and is aimed at spurring non-profit housing construction. The RIP also removes parking mandates from three-quarters of residential land.

The dream of a detached home with a large front and back yard within the city limit is no longer affordable to more than the most fortunate few.

The Mayor’s office in the City of Vancouver recently proposed a pilot program that would allow similar higher density (four to six units) permitted on detached lots. At the moment the plan is short on details, but such a shift would be consistent with the idea of incremental “gentle density” increases.

The case for higher density is straightforward: the dream of a detached home with a large front and back yard within the city limit is no longer affordable to more than the most fortunate few. As Jens Von Bergmann summarizes for the City of Vancouver: “35% of all households live on single family and duplex properties making up 81% of Vancouver’s residential land, while the remaining 65% of households live on 19% of the residential land.” Allowing more units per lot thus allows expensive land to be divided across more households.

This call is getting support at the highest levels, including from Evan Siddall, president of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, who suggested we need to go even further:

I’ll be frank: we are far from convinced that … “gentle densification” … is going to move the needle significantly in making housing more affordable for people in land-constrained cities like Toronto and Vancouver. Aggressive — even disruptive — densification will be necessary if our cities are to continue to serve as engines of economic growth, innovation and job creation that benefits all Canadians.

Higher densities are also justified from a climate action and environmental perspective. Single-family housing in many instances necessitates the use of a car as the main mode of transportation. More dense forms, on the other hand, can contribute to an overall lower carbon footprint to the extent that they support “complete communities” – neighbourhoods where people live in much closer proximity to where they work, shop, access public services and play. The per-unit cost of infrastructure (e.g. utilities, roads, storm drains) is much less in more dense developments, and energy costs are greatly reduced through shared walls and smaller unit sizes. In more compact communities, it also becomes possible to reduce or even waive parking requirements for cars, a non-trivial expense that can range from $42,000 to $63,000 per space.

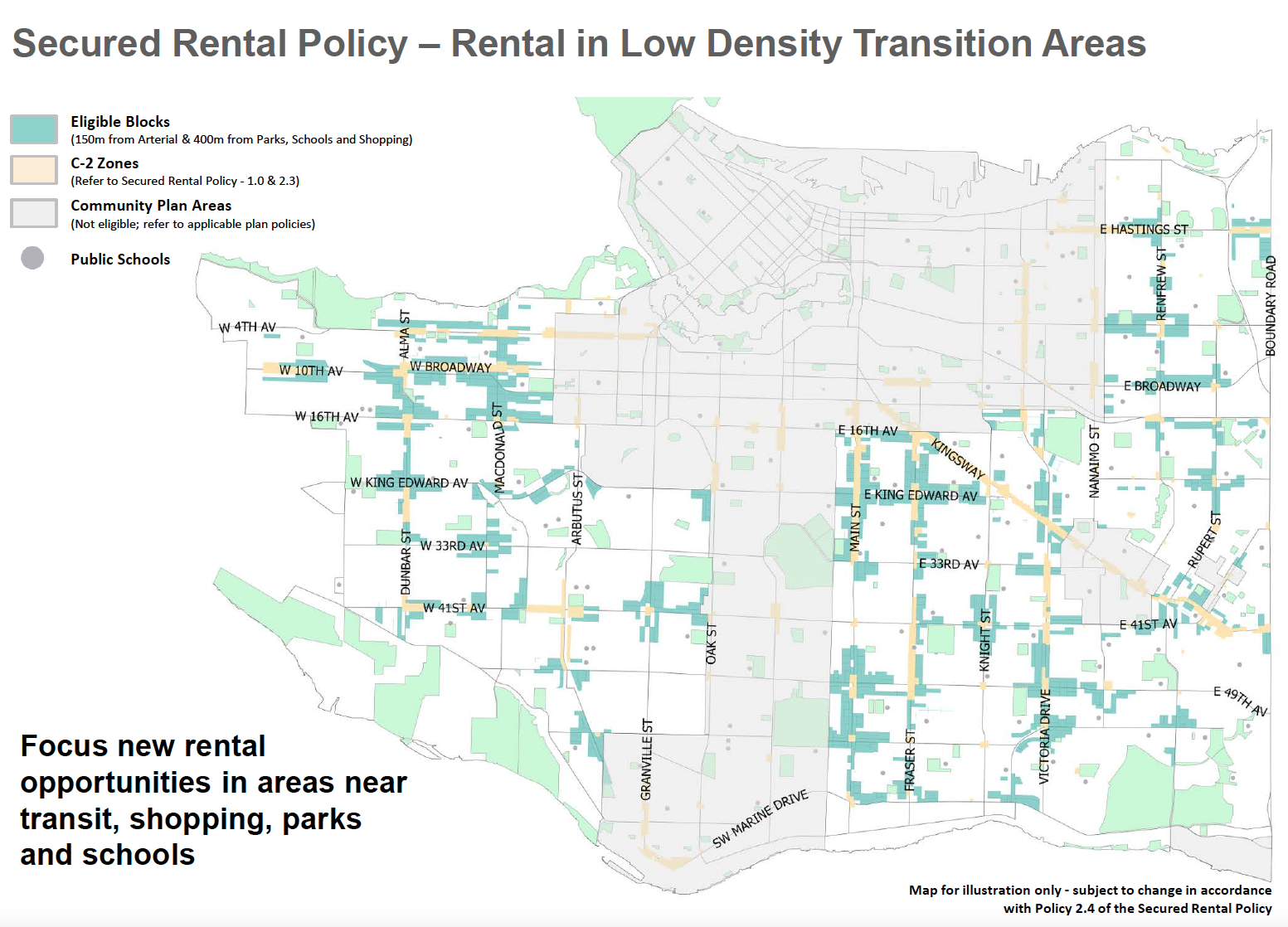

Note: The SRP does not cover a number of central areas currently covered by other neighbourhood plans and by forthcoming plans (Broadway corridor, Skytrain stations) Source: City of Vancouver

The Secured Rental Policy

The Secured Rental Policy (SRP) was tabled in the spirit of increasing market rental housing supply, in line with targets in the City’s housing strategy, while also meeting climate emergency goals and creating more vibrant urban locations. After decades of condo development, the focus on rental is welcome. More than half of households in the City of Vancouver are renters who have seen no benefit from rising home prices and, if anything, have been made worse off due to an ultra-low low vacancy rate, rising rents and renovictions/demovictions.

The SRP introduces two major changes. First, it will permit up to six-storey buildings with 100% rental on main streets (technically known as C-2 zones which include ground-floor shops) without a rezoning. This extra density is to encourage developers to choose rental over four-story strata/condo development that continues to be permitted. Second, a two-year Low Density Transition Areas pilot will allow up to four-storey 100% rental buildings (apartments and townhomes) just off of main streets—up to 150 metres away and 400 metres from a school (the historically low-density RS and RT zones). A streamlined rezoning process will apply.

The significance of the SRP was perhaps obscured by a 236-page staff report, blandly titled Rental Incentives Review Phase II Report Back, which accompanied the policy approved by council (now consolidated on this webpage). Specific details and by-law changes are in progress (delayed by COVID-19) and will go to public hearings and final approval by council later in 2020. As the figure shows, the SRP does not include other new density that will be added through recently approved community plans (e.g. Grandview-Woodlands and Cambie Corridor), nor the forthcoming Broadway plan and neighbourhood-area plans around the Nanaimo and 29th Avenue Skytrain stations.

More than half of households in the City of Vancouver are renters who have seen no benefit from rising home prices.

The SRP builds on more than a decade of rental incentives the City of Vancouver has provided to encourage market rental housing. While the city saw abundant rental housing built between the mid-1950s and 1970s, changes in the federal tax system and the advent of stratified properties (condos) shifted the economics for property developers towards building more profitable condos rather than rental. Negligible rental housing was built in the 1980s to 2000s. In recent years the City has aimed to move the needle back to rental by providing a package of municipally controlled incentives—such as reduced parking requirements, waiver of development levies and allowing greater density. It has achieved some modest success with 8,680 rental units built over the past decade.

The new SRP has been supported by developers and market urbanists, although some argue the policy does not go far enough in terms of height and density on the one hand and geographically on the other. City staff argued that the explicit focus on rental would not translate into higher land prices and will thus avert land speculation and windfall profits going to existing landowners. In the same vein, a number of developers have questioned whether much rental will get built under this policy due to Vancouver’s high costs of land and construction.

Concerns about the SRP include the potential impact on the character of existing neighbourhoods, and around gentrification and displacement of existing renters. The potential loss of older, more affordable suites to a greater number of less affordable dwellings is a concern. Some commentators felt this could have a negative impact on secondary suites that would disproportionately affect ethnic communities in Vancouver. In such cases, affordability through increased supply may only be theoretical.

Where should new density go?

The Low Density Transition Areas part of the plan is important because new rental has too often been located on main streets, exposing renters to noise and air pollution. This is also the most politically challenging part of the plan because it directly targets existing low-density neighbourhoods.

In areas that are already above-average density, some concerns could be addressed by measures that enable more rental units within existing structures like four-storey heritage homes (a “gentle density” approach). Kitsilano residents, for example, have been vocal about the new SRP’s impact, and it is notable that Kitsilano has a residential density of 7,884 people per square kilometre, compared to the city average of 5,493.

At 1,890 people per square kilometre, Shaughnessey is the lowest-density neighbourhood in the City of Vancouver and its low density is protected under its own heritage zoning. Given that this neighbourhood currently houses so few and is walking distance from Broadway and downtown, there is a strong case to be made against preserving homes for the super-rich in Shaughnessy. The city could lead a process of purchasing and assembling land, then upzoning to allow rental apartment buildings. The city could then build them directly or sell to private sector developers.

While Shaughnessey is an extreme case (and not directly in the purview of the SRP), other low-density areas could come first in terms of upzoning. For example, Jens von Bergmann and Denis Agar consider a framework for “planned displacement” by mapping the areas of Metro Vancouver close to the Frequent Transit Network by the number of renters. Some displacement is inevitable due to new development, but harms can be minimized by concentrating new development in low-renter-density places, and ensuring that new projects do not displace existing rental or non-market housing.

Protecting rental and renters

The SRP comes in addition to many other projects and pilots the City of Vancouver is doing on housing. The City has led with its Empty Homes tax, regulations on short-term rentals and other housing incentive programs, such as Moderate Income Rental Housing Pilot Program (for 20 buildings with 100% secured market rental housing, and a minimum of 20% permanently secured for moderate income households) and the creation of a new Affordable Housing Endowment Fund. These efforts have occurred in spite of a lack of meaningful engagement from the BC and federal governments, in particular the failure to fund dedicated, affordable non-market housing.

The path forward should not only be about housing supply in the aggregate and abstract, but what type of housing and for whom. Current low-density zoning primarily benefits existing property owners, and a worse situation would be for blanket upzoning to permit market condo development, which would lead to huge windfalls to homeowners. Ultimately, it’s less about whether we upzone but what that looks like, and what protections are put in place to mitigate problems.

Redevelopment from upzoning has the potential to displace vulnerable people currently paying reasonable rents and who may not be able to afford an increase. This concern must be weighed against the reality that renters face today: high market rents and the need for more supply to prevent rents from escalating further. Existing affordable rental housing in the form of three- or four-storey walk-ups should be protected as much as possible—at least for the next decade—so that the emphasis of redevelopment can be on transforming single-family lots. New rental housing shouldn’t need to come at the expense of existing rental housing.

The path forward should not only be about housing supply in the aggregate and abstract, but what type of housing and for whom.

For any development that does occur, robust tenant protections will be necessary. The City has a one-for-one rental housing replacement policy that should be amended to address this potential issue, and the City is also funding a pilot to reinvest and improve older rental buildings with energy efficiency upgrades. In June 2019 it also tabled a package of improved renter protections and compensation, including increased compensation for renters, and tenant protection for renters in detached homes where two or more lots are being assembled for redevelopment.

Recent moves by the City of Burnaby show a change in direction after many years of condo development leading to the removal of older and cheaper rental housing stock (consider the redevelopment around Metrotown station). Renter protections include:

- Ability of tenants to return to their units at the same rent in the event of renoviction.

- Right of first refusal for a replacement unit after a demolition.

- Displaced tenants are offered moving assistance (maximum of $750 for bachelor and one-bedroom suites and $1,000 for two or more bedrooms.)

- Temporary accommodation at “swing sites” and/or a rent “top up” to bridge the difference between current and temporary rent.

While this framework hits the right notes, one caveat is that provisions only apply to buildings with six or more units. Of note, the planning framework echoes that suggested by the 2017 People’s Plan for Metrotown, which would sequence development and protect people in existing rental buildings by: first developing single-family lots in the vicinity into multi-family buildings; moving renters to the new units while older rental stock is redeveloped; then allow them to move back to the new units.

Non-market housing needed

While the SRP is aimed at the development of market rental, substantial non-market rental will also be needed because market rents in new buildings are too high for many low- to moderate-income households. Non-market and co-op housing should be central to the build-out. In previous research we call for 10,000 non-market rental units per year to be built in Metro Vancouver to alleviate the current imbalance in the housing market, and that building for low- to middle-income households is not profitable to private sector developers.

The biggest barrier right now is a lack of senior government investment in non-market housing for low- to middle-income households. However, a more ambitious city-led program could include public housing development, land assembly and land banking. The Vancouver Affordable Housing Agency combined with the new Affordable Housing Endowment Fund have the key ingredients for a more active public sector player that can build housing we need locked in at lower, more affordable rents in perpetuity.

The biggest barrier right now is a lack of senior government investment in non-market housing for low- to middle-income households.

Fair taxation of property wealth, and in particular windfall gains, is also essential to raising revenues that can be spent on buying land for new affordable housing and compensating households that are displaced. Shifting to a more progressive system of property taxation should include measures to increase taxes on high-value properties, shifting more of the tax load to land as opposed to buildings, and increasing taxes on properties held by those who do not live and work in the city.

Finally, there is a knock-on impact of higher density on schools, libraries and community centres. In recent decades capital costs of these have been supported by development cost levies and community amenity contributions. These are generally waived for projects under the SRP so we need to fund such amenities more out of property taxes rather than development charges. Transportation is another area to be considered, and the general pattern of upzoning can create conditions for new transit lines to support population growth and improve mobility across the city.

The SRP signals that the fight over density is coming to low-density neighbourhoods. Done well, it has the potential to create more affordable housing and more climate-friendly communities. But many transition issues need to be front and centre to minimize adverse impacts on renters and existing affordable rental housing.

This post is a part of an ongoing research project into affordable housing funded by the Vancouver Foundation.

Topics: Housing & homelessness, Municipalities