Swimming against the tide

The challenge of higher interest rates and high household debt

The run-up of interest rates since March, led by the Bank of Canada in a bid to tame inflation, represents a substantial economic shock, one that is now pushing the country towards a recession. The bank’s overnight, or policy, interest rate is now at 4.25 percentage points, up from 0.25 per cent in February.

This has cascading effects on other interest rates like mortgages and personal loans that matter for Canadian households. Sky-high household debt acquired during a period of low interest rates now needs refinancing at much higher rates.

As this research will show, the higher costs of servicing outstanding mortgage and other consumer debt in 2023 are equivalent to almost two per cent of GDP. That’s a powerful macroeconomic riptide to swim against and only one aspect of the economic downturn now underway. Let’s take a look behind the numbers at this abrupt shift in monetary policy and why it will necessitate large federal and provincial fiscal responses in 2023 budgets.

How did we get here?

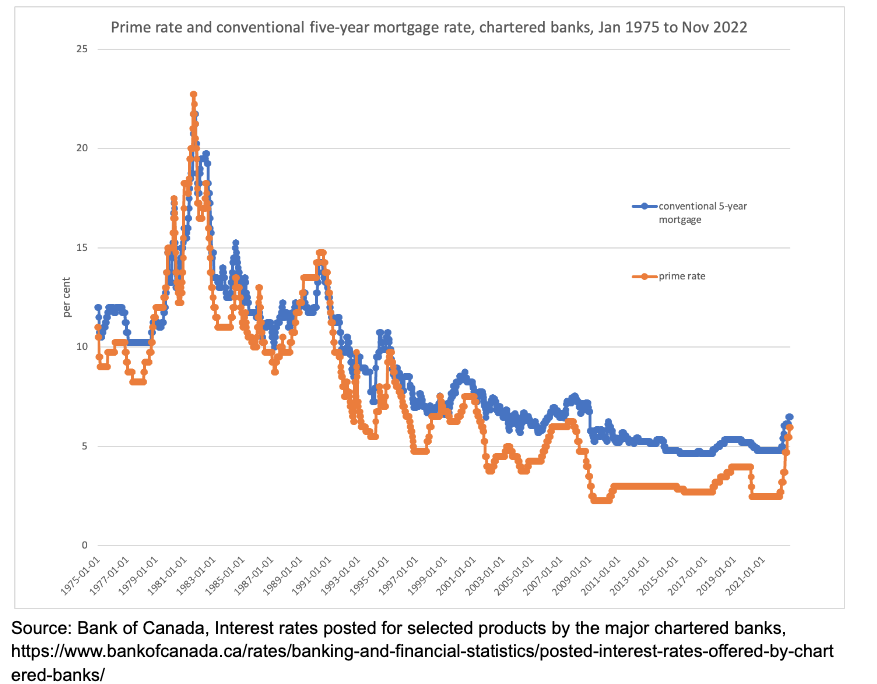

Rate hikes through 2022 represent a stunning reversal from a decade of low interest rates. The recent period of ultra-low rates in the wake of COVID-19 shutdowns in March 2020 is top of mind, but interest rates have been historically low since the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

As the figure below shows, today’s higher rates are still low in relative terms. Back in the 1980s, interest rates soared due to central bank efforts to stamp out 1970s inflation. Much of the Bank of Canada’s current effort stems from fears of reliving the 1970’s and 1980’s experience with inflation and interest rates.

Figure: The long view of interest rates

Over the past 20 years, a low-inflation environment shifted the role of the Bank of Canada. Rather than taking away the punch bowl when the party gets roaring, to keep inflation at bay, instead the Bank has been involved with extraordinary interventions to prop up the economy. In both the 2008 financial crisis and 2020 COVID-19 shutdowns the Bank lowered interest rates to provide liquidity and stimulus to the economy.

Cheap borrowing costs were a big reason why home prices swelled over the past two decades, as buyers could take on larger mortgages. Low interest rates also fuelled speculative behaviour in housing with investor purchases of secondary residences and rental properties, but also with tech stocks and shady digital assets like Bitcoin and NFTs (non-fungible tokens).

Interestingly, the Bank of Canada was blasé about soaring real estate prices and cryptocurrencies in 2021. Only when consumer price inflation reared its head in 2022 did the Bank spring into action, even though by its own admission two-thirds of inflation is due to factors outside of Canada’s borders, most notably the price of oil in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and supply chain backlogs due to COVID-19.

The Bank has pushed an old monetarist line about too much money in the hands of workers causing inflation, a claim that is not credible. Indeed, the Bank seems all too willing to throw workers into unemployment and the economy into recession to achieve its objective of a return to low inflation.

The interest bite of higher rates

Canadian households have taken on a lot of debt that must now be refinanced at much higher rates. As of September, Canadian households had more than $2.8 trillion outstanding in debt, of which $2 trillion is mortgage debt. For reference, Canada’s GDP in 2022 is about $2.7 trillion.

High debt levels spell trouble for about one-third of the population who are homeowners with a mortgage, in particular households with high mortgage debt relative to income. For example, a household with a $500,000 variable rate mortgage will be paying $20,000 per year in additional interest with increased rates of four percentage points since February 2022. This interest bite applies to other household debt (e.g., personal loans, lines of credit and credit cards) as well.

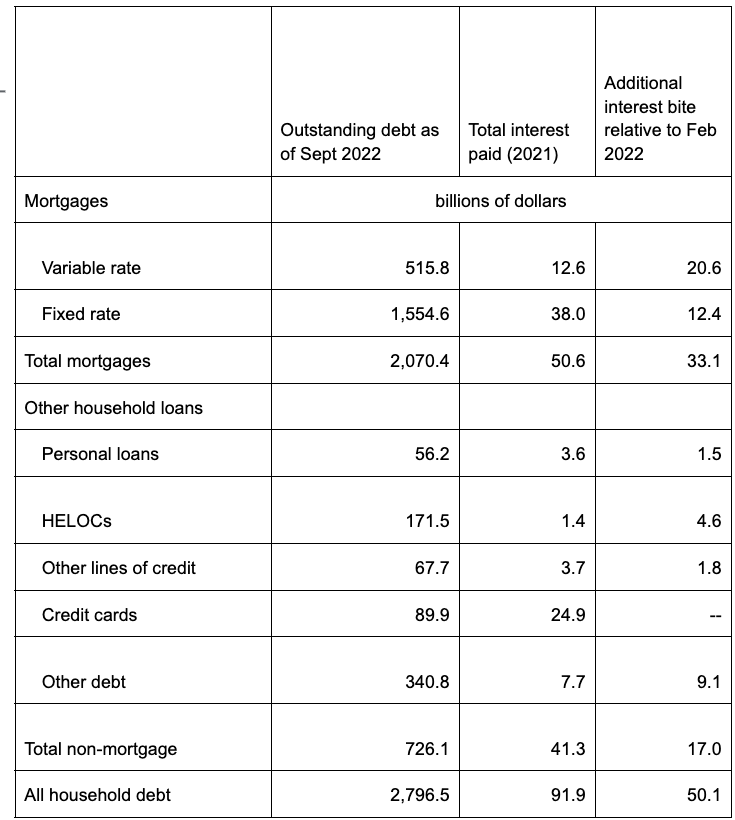

The macroeconomic impact of refinancing household debt is significant. The table shows outstanding debt for several categories of mortgage and non-mortgage debt, interest paid and a projection of additional interest costs at the full four percentage point interest rate hike. Credit card rates are an exception, as they generally have fixed (albeit very high) interest rates.

Some debt is retired each year, and higher rates may push some to retire debt early before getting hit by higher rates. About two-fifths of outstanding mortgages are on fixed terms greater than five years and are thus the most insulated from the interest rate shock.

On the other hand, more than one-third of the outstanding mortgage debt—some $516 billion—is at variable rates. Much cheaper variable rates compared to fixed led to more than half of mortgages issued at a variable rate in the second half of 2021 and first half of 2022.

Table: The interest bite from higher interest rates

Notes: Interest paid for total mortgages and total non-mortgages are from Statistics Canada, household sector data, but the sub-categories for interest paid are author’s estimates based on SC funds advanced and outstanding balances data. For interest bite, we assume 100% of variable rate mortgages, 20% of fixed rate mortgages and 67% of other household loans are affected by higher rates. HELOCs are Home Equity Lines of Credit. Credit cards have mostly fixed rates so they are not affected by the rate hike.

Sources: Statistics Canada, Funds advanced, outstanding balances and interest rates for new and existing lending, Table: 10-10-0006-01. Statistics Canada, credit liabilities, Table: 36-10-0639-01. Statistics Canada, Household sector, selected indicators, provincial and territorial.

Outside of mortgages, other household debt is substantial at $726 billion. This non-mortgage debt generally pays higher interest rates than mortgages, and increases over 2022 may be less than the full four percentage point increase from the Bank of Canada.

Nation-wide, households paid $50.6 billion in mortgage interest and $41.3 billion in non-mortgage interest in 2021. We can estimate the additional interest bite by applying four per cent to various outstanding debt balances. This is a simplification as particular interest rates will change based on length of term, risk and type of lending (called the yield curve). We assume one-fifth of fixed-rate mortgages and one-third of other (non-credit-card) consumer debt will roll over at higher rates next year and 100 per cent of variable rate mortgages.

Factoring in the full four percentage point increase in 2022, mortgage interest payments will shoot up to $84 billion, and non-mortgage interest payments to $58 billion. This incremental interest bite of $53 billion is equivalent to almost two per cent of GDP and will undercut household spending on other goods and services.

For variable rate mortgages, the interest bite gets spread out over time as fixed monthly payments may stay the same but less will be paid to reduce the principal and it will take longer to pay off the mortgage (increased amortization). Some with variable rates will see their monthly payments rise if they surpass a trigger rate where fixed payments cover only interest and not any repayment of principal. According to a November 2022 Bank of Canada analysis about half of variable rate mortgages were already at their trigger rate.

Higher interest rates represent a windfall for the banks and show that high interest rates are good for the rentier class that makes its profits lending money. On the other hand, in a deeper recession the banks may soon have their hands full dealing with overextended customers. And in current market conditions, the number of new mortgages coming in the front door has stalled.

The need for deficit spending

The era of low inflation and low interest rates is over, for now. While the Bank of Canada is pitching a “soft landing,” the substantial headwinds associated with household debt, as outlined here, are significant and represent only one source of economic contraction. As real estate and stock prices fall with rate hikes, the wealth effects that propelled new spending when asset prices were rising (because people feel better off) are now moving in the opposite direction. That will lead to households pulling back on spending. Moreover, higher borrowing costs and a diminished future outlook will also lead to reduced investment by businesses.

Provincial and federal governments will need to run large deficits to lean into this baked-in contraction in the economy. Already, the fiscal positions of federal and provincial governments have been contractionary as COVID-19-oriented fiscal stimulus has been unwound over the past year to 18 months. Many conservative voices will be calling for government belt-tightening, but instead we need governments to do the precise opposite or recessionary pressures facing the economy will be reinforced.

Many households believed the Bank of Canada would keep interest rates low and almost no one a year ago expected the severe tightening we have seen in 2022. These hikes may or may not help reduce inflation, but one thing is clear: households are going to be hurting under the weight of higher rates in 2023.

Topics: Economy