Indigenous resurgence in a province like no other

After 30 years of treaty talks, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings, and the adoption of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, First Nations still face racism on a systemic basis. Can Indigenous People ever find justice in this province?

John Price and Nicholas XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton, co-authors in the new book Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, suggest that reconciliation will remain elusive unless the issue of Indigenous sovereignty is recognized as central and properly addressed.

This is the third part in a three-part series, where the authors review how the 1871 Terms of Union that brought this province into Canada affected Indigenous peoples, how Indigenous people have fought for sovereignty before and after, and why new initiatives directed at recognizing and institutionalizing Indigenous sovereignty may be the only path leading to justice and reconciliation. Part one and part two were previously published on this website.

Before Europeans arrived in the Pacific Northwest, the W̱SÁNEĆ people were highly networked, particularly with other Salishan-speaking peoples of the area. Trading, kinship ties and strategic alliances allowed the sharing of resources.

These ties became increasingly important, expanding beyond the large Salishan language group to form the basis for a unique and powerful Indigenous resurgence in the face of B.C.’s rogue policies.

In 1871, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald appointed none other than Joseph Trutch, the main architect of Indigenous dispossession in B.C., as the province’s first lieutenant-governor.

Macdonald also pushed through the 1872 disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples and Chinese Canadians, representing 80 per cent of the population, despite protests from Premier John McCreight.

It dawned on federal officials, however, that what had “hitherto been the practice” of the province regarding land title differed from existing federal policy, that is, to sign treaties in order to extinguish aboriginal title.

Visiting the province in 1876, the governor-general, Lord Dufferin, expressed federal frustration: “Most unfortunately, as I think, there has been an initial error ever since Sir James Douglas quitted office … of British Columbia neglecting to recognize what is known as Indian title.”

The province adamantly rebuffed federal objections and by 1880 any thought of changing the province’s policies had vanished. As scholar Cole Harris put it: “Almost a decade after it began, the dispute between Ottawa and Victoria over the Indian land question was essentially settled. The province had won.”

The federal policy was to recognize limited Indigenous title to extinguish it — the province wanted to ignore it entirely, and did so — denying any form of Indigenous sovereignty or title, repudiating treaties, allocating the smallest reserves possible, and reducing existing reserves.

The province was taking land from Indigenous peoples and giving it to settlers, to railway companies, and to forest and mining companies at a breathless pace.

Adding insult to injury was the federal Indian Act of 1876, the 1888 ban on the Potlatch, residential schools, and hunting and fishing regulations that severely affected Indigenous food security.

W̱SÁNEĆ leaders came together with other Salish communities in the 1890s to discuss how to best resist colonization’s effects. At the same time, communities in the north, notably the Nisga’a, began organizing as well, leading to a province-wide Indigenous resurgence.

Indigenous resurgence

“We come before you to-day as the Chiefs and Representatives of nearly all Indian Tribes throughout the Province of British Columbia. We do not come to you as a body of settlers, but as the original inhabitants of this land. Our ancestors have occupied this country from time immemorial; and we their children claim that the Indian Tribes still hold the aboriginal title to the unsurrendered lands of the Province, which has never been extinguished, either by conquest or treaty.”

It was the manifesto of an Indigenous resurgence that continues to this day.

W̱SÁNEĆ leaders Chief David Latess and Thomas Paul both signed this petition along with nearly 100 other chiefs and delegates. They came to Victoria in March 1911 to demand the premier of the day, Richard McBride, recognize their title to the land.

Contrary to McBride’s public assertions that Indigenous people in the province were “well satisfied,” they let him know “our people are far from being satisfied, and are becoming more dissatisfied every day.”

They wanted their claim to title to be “submitted to the Courts.” McBride refused, stating “Indians had no title” and therefore there was nothing for the courts to decide.

The 1911 Victoria gathering to confront McBride was preceded by major local protests, as well as earlier petitions and delegations demanding land justice, including a 1904 delegation to the Vatican, and a 1906 delegation to King Edward in London.

The late Dave Elliot recalled that reef-net fishing, a form of open-ocean netting of fish over reefs, traditional to the W̱SÁNEĆ and Songhees, was banned, as were other Indigenous forms of fishing.

Indigenous communities across the province came out en masse to government hearings aimed at “adjusting” reserves (McKenna-McBride commission, 1913-1916) and the records of those proceedings echo loudly with ancestors’ protests.

The resurgence that had begun at the turn of the century culminated in the formation of the Allied Tribes of B.C. in 1916. Led by Peter Kelly (Haida) and Andrew Paull (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh), the Allied Tribes represented most communities, including the W̱SÁNEĆ.

The Allied Tribes categorically rejected the McKenna-McBride report. The organization’s dynamism and legal acumen in fighting for land rights led the federal government to amend the Indian Act in 1927, introducing Section 141 preventing legal actions to support land claims.

Dispossessed, disenfranchised, and stripped of access to the courts, First Nations faced desperate times.

Beyond survival

The fires of the first Indigenous resurgence were reduced to embers with the legal lockdown imposed by the federal government in 1927. The next two decades were harsh as Indigenous organizing went underground to a large extent.

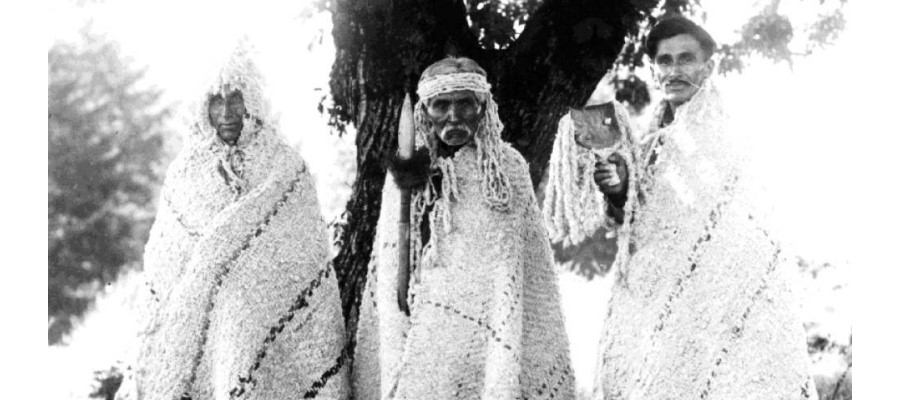

Born in 1915, Laura Olsen was instrumental in helping the W̱SÁNEĆ survive this difficult period. Her son, Carl, recalls: “What she did was knit so we could eat. There were 12 of us and there needed to be a way to supplement my dad’s income. He was a fisherman and logger but the wages weren’t that good. With his work, he paid the bills. With her work, she made the meals. All of her knitting was to put food on the table.”

Laura was only one among many W̱SÁNEĆ and Cowichan knitters who kept body and soul together during hard times. And she, like others of her generation, had more children, allowing the family and community to make it through these disastrous years,

Then, the postwar repeal of Section 141 of the Indian Act allowed legal cases to go forward once again. By the 1960s, a second resurgence was underway. Today, the names of Peter Kelly, Andrew Paull and George Manuel are gaining greater recognition as Indigenous leaders of this era. Add to that list W̱SÁNEĆ Chief Philip Paul.

Born in 1933, Philip Christopher Paul attended the Kuper Island Residential School that he later recalled “attacked his language, spirituality, and freedom of thought.” After working in the munitions plant on James Island, now the subject of a land claim on the part of the W̱SÁNEĆ, Paul went on to become active in the community, becoming chief of Tsartlip and bringing with him a vision based on the need for cultural revitalization and collective action.

By 1967 he was the director of Native Studies at what would become Camosun College in Victoria. A close ally of Indigenous rights leader George Manuel, he helped found the South Vancouver Island Tribal Federation in 1965 and the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs in 1969. He was head of UBCIC lands claims research to 1975 and education director from 1977 to 1980.

Paul, with George Manuel, Bob Manuel and many others, organized the now famous Constitution Express, the cross-Canada train demonstration to Ottawa, leading to the inclusion of Section 35 on Aboriginal rights in the 1982 Constitution. This victory, subsequently applied in B.C. legal cases, was a first step on the road to Indigenous sovereignty.

Paul never forgot his community, however, and played an instrumental role in founding the Saanich Indian School Board and the Tribal school, the base for revitalization of the W̱SÁNEĆ language, SENĆOŦEN. His work and that of the late Dave Elliot revitalized the language, nurturing a new generation of native speakers and teachers.

When the province finally agreed to engage in land claims discussions, the W̱SÁNEĆ were ready, adopting a 1987 Territorial Declaration: “We, the Saanich Indian People, declare on this Eighth day of January, Nineteen hundred and eighty seven, that we hold the absolute rights and title to our Territorial Homeland as indicated on the accompanying map of which all our territory is named in the SENĆOŦEN language. We do not recognize any past attempts to separate us from our homeland. We recognize there were Treaties of Peaceful Co-existence entered into with the early settlers but this did not involve the sale of rights or land.”

Like many Nations, the W̱SÁNEĆ left treaty talks after it became apparent that the government was determined to extinguish their sovereign rights over their traditional territory. But that has not prevented the community from moving forward in reclaiming its land and its heritage.

Its program of cultural revitalization through education is vibrant. Wherever the Nation gets involved, its representatives make it clear that W̱SÁNEĆ retain sovereignty over their traditional territory that extends over much of the southern Gulf Islands.

And the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council, representing the Tsartlip, Tseycum and Tsawout communities, is regaining title to SISȻENEM (Halibut Island), a 9.7-acre property to the east of Sidney Island. Purchased recently by the Land Conservancy of British Columbia, it was voluntarily turned over to the W̱SÁNEĆ people.

Chief Don Tom, chairman of the Leadership Council, heralded this move as a meaningful step in that it shows that reconciliation is everyone’s responsibility. Similar non-governmental actions will help preserve the environment and help heal the W̱SÁNEĆ people, he said.

From the 1911 confrontation with then-premier McBride, to the fight to stop TMX, to the battle to defend the traditional territory of the Wet’suwet’en, the W̱SÁNEĆ are part of an ongoing Indigenous resurgence against the policies of “British Columbia” — a province like no other.

Nicholas XEMŦOLTW̱ Claxton and John Price and are co-authors with Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra, Denise Fong, Fran Morrison, Christine O’Bonsawin, and Maryka Omatsu of Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, available as a free download at challengeracistbc.ca.

This article was originally published in the Times Colonist.