Assessing BC’s Fiscal Health: Can BC afford more deficits?

By Seth Klein and Iglika Ivanova [Note: this piece has also appeared in the Tyee here.]

OK, time for a reality check on BC’s deficits.

Simply put, while arguments about deficits and “who is the better fiscal manager” may make for entertaining politics, there is no compelling economic reason why BC cannot run a few years of modest deficits. And in the absence of deep cuts to services, whoever wins the May election would have to run a deficit – that’s the legacy of tax cuts that have deprived the public treasury of revenues needed to adequately fund our public services.

Understanding the difference between deficit and debt

First, a bit of economic literacy: understanding the difference between “deficits” and “debt”.

A deficit (or conversely a surplus) is the difference between what a government collects in revenues and what it spends on its operations in a given year (capital spending, that is to say infrastructure investment in building schools, hospitals, bridges etc., is typically not included in the operating accounts and does not add to the deficit). Government debt, on the other hand, is the accumulation of annual deficits, plus capital spending on infrastructure projects, plus interest payments on previously incurred debt. For example, in the fiscal year that just ended, BC is forecast to have had a deficit of $1.2 billion (a finalized figure will be known in a few months). But provincial taxpayer-supported debt is forecast to be $38 billion for the year that just ended, and $42.5 billion this year.

These are big numbers. But government budget figures always are. And they can be a bit distracting. Because what really matters isn’t the absolute size of these numbers, but rather, their relative size. Meaning, how do these numbers compare to our ability to pay? For example, if one considers this in personal or household terms, what matters isn’t the actual amount of dollars that someone’s debt is, but rather how that debt compares with their income, and second, whether those debts were accumulated for good reasons – were they wise investments?

That’s why economists (and bond-rating agencies) aren’t particularly interested in a government’s deficit or debt, but rather, in the debt-to-GDP ratio (meaning, the debt relative to the annual income of the economy) or in debt service costs (meaning, debt interest payments relative to the size of the budget). These are the figures we need to look at to get a meaningful picture of a government’s fiscal health. They capture whether a debt is comfortably manageable, or conversely, alert us if the debt becomes problematic.

And if debts are accumulated to improve the health of a society, to invest in education, to protect the environment and sustainably manage shared resource assets, or to build needed infrastructure that will be in use for many years to come, then they should rightly be seen as wise investments. That’s because these are all forms of spending that enhance the long-term productivity of a society – they allow us to create more wealth in coming decades. Indeed, if a society fails to make such investments, it risks being much poorer over time. That’s why investing in things such as poverty reduction, child care and early childhood education, more specialist teachers in the K-12 system, post-secondary education, environmental stewardship and climate action makes good public policy. Failing to make these investments today is a false economy – it makes the books look good today, but it sets us up on a path of lower productivity, increased social ills and higher total costs over the long run.

BC’s debt level is manageable

So, having clarified those concepts, what is the BC situation?

In short, BC’s fiscal position is quite manageable. And we can comfortably afford to run modest deficits for a number of years.

Notably, while much is made of provincial government operating deficits, the rise in provincial debt has been driven much more by capital spending on infrastructure than by annual budget deficits. For example, while last year’s deficit was $1.2 billion, taxpayer-supported capital spending totaled $3.7 billion, as has been the trend for many years.

In the charged environment of an election, there is a risk of deficit and debt hysteria making an unwelcome comeback. Shock value is sought when noting that BC’s debt is at “an historic high” (in straight dollars), without noting that our economy and population have also grown.

While BC’s taxpayer-supported debt is projected to be about $42 billion in 2013/14, we are a wealthy province with an annual income (GDP) of well over $200 billion (projected to be $233 billion in 2013). That puts our debt-to-GDP ratio at about 18% –– which is pretty good on the heels of a recession –– and is projected to stabilize at that level over the next couple of years. It’s not an historic high, and, in fact, it’s the envy of most other places, as the charts below show. As the first chart shows, BC’s debt-to-GDP is the third lowest in Canada.

Source: TD Economics. 2013. Government Budget Balances and Net Debt as of Mar 27, 2013.

Yes, BC’s debt-to-GDP level is now higher than the 13% we reached in 2008, but this shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. We just went through the deepest recession we’ve had in 30 years. Of course debt would be higher than what it was during the boom — that’s what should happen.

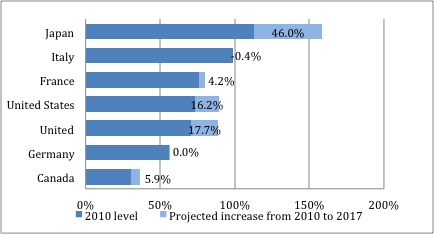

And as the second chart shows, debt levels in Canada are in turn among the lowest in the industrialized world.

Total Government Net Debt as a share of GDP (G7 countries)

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook (October 2012).

BC spends about 4 cents for every dollar of government revenues on interest on the taxpayer-supported debt (see Table 1.16 in the BC budget). Again, entirely manageable. (If most of us were only spending 4% of our personal incomes on debt interest, we’d be pretty happy!)

Indeed, in the current environment of low interest rates, now is an ideal time for the government to borrow in order to invest in improving the economic security and future productivity of British Columbians.

Wise investors also compare the rates of return on different investments. That’s why it’s too simplistic to say that governments should prioritize eliminating deficits and paying down debt. Such a policy course needs to be compared with other options.

At the household level, going into debt often makes sense, if, for example, it means building a rental suite that provides income over time, or investing in a child’s post-secondary education and thereby improving their lifetime earnings.

The same logic holds for a government. Consider this: the rate of return on debt-reduction is the interest rate we pay on the debt (this is how much the province would save if we were to pay down a portion of the debt). The long-term interest rates the province pays on its debt are around 4 to 4.5%. In contrast, many public investments (such as spending on education) have higher rates of return than that, which makes them better candidates for government spending than paying off the debt.

A cautionary note: the government record of increasing “contractual obligations”

While taxpayer-supported debt is currently forecast at $42.6 billion, when the debt of “self-supported” Crown corporations is added, BC’s debt rises to $62.7 billion.

However, not included in this figure (nor in the BC Budget itself; only in the Public Accounts) is the huge ramp-up that has occurred in recent years under what the government calls “Contractual Obligations.” These now amount to over $96 billion, most of which has been accumulated over the last six years.

Omitting this from the BC Budget represents a stunning lack of transparency. These obligations are the product of building infrastructure via public-private partnerships (P3s). The largest chunk (about $60 billion) results from BC Hydro signing long-term electricity contracts with private power companies. But a sizeable share also represents long-term P3 developments such as the Canada Line and Abbotsford Hospital. Our “obligation” comes in the form of a decades-long commitment to made annual lease payments, but this is government debt by another name. And hiding these commitment from the Budget is simply fiscal trickery.

To be clear, many of these infrastructure projects were needed and worth doing. But doing them as P3s has inflated the long-term costs (as we end up paying more in interest and in profits to these private “partners”). And those liabilities should be clearly visible in the government’s books.

But even with these long-term obligations, BC’s debt is still manageable. Most of those lease payments and contractual fees are spread out over 30-40 years. The ones carried by BC Hydro will certainly cause us all some headaches in the coming years, and will be a big reason for escalating Hydro rates for consumers. We will need to figure out how to pay for them in an equitable manner. But as a society, we can afford them.

Given the social, economic and environmental challenges currently facing our province, a focus on reducing the deficit and paying off debt at the expense of strategic public investments is short-sighted. Our government’s credit rating is excellent, our debt level is manageable and there are a number of strategic public investments that will make British Columbians better off and improve our economy in the future. What better time to invest than now?

Topics: Economy, Provincial budget & finance, Taxes