What’s the real story behind BC’s education funding crisis?

This spring school boards across the province experienced budget crises, raising questions about funding for elementary and high school education in BC (kindergarten through grade 12). Despite provincial government claims that education funding is “at record levels” funding has actually shrunk substantially as a share of BC’s overall economic pie, and fallen almost $1,000 per student below the Canadian average. Meanwhile, enrolment is projected to rise; the government estimates that there will be 40,000 more students by 2024.

School closures, disjointed one-off funding announcements and school board budget crises are not necessary or inevitable. In BC, the numbers show we can afford to invest strongly and stably in education. Underfunding is a political choice.

Is education funding “at record levels” or in crisis? Rhetoric and reality clash

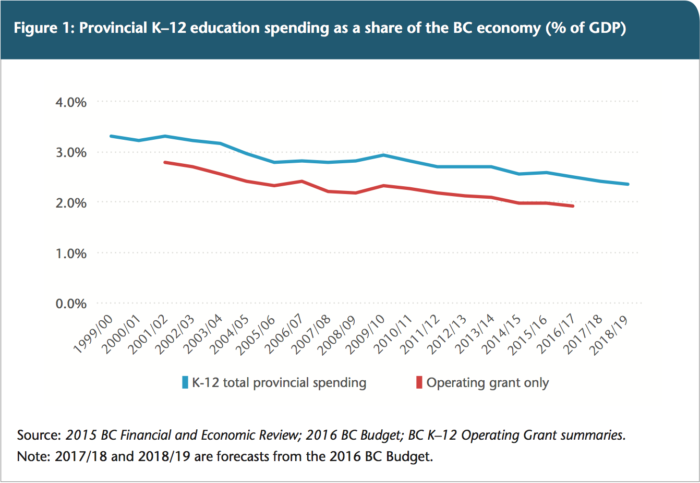

We see a significant drop in the share of our total economic resources dedicated to public education, from 3.3% of our province’s GDP in 2001 to a projected 2.5% in Budget 2016 — a 25% decline.

Yet, although Vancouver has been the most visible example, at least half of BC’s local school boards have faced budget crises this year,1 with many forced to close schools and impose other cutbacks to balance their budgets as required by provincial law.

Meanwhile, following a familiar strategy of concealing taxes by calling them “fees,”2 the education system continues to rely on parents3 to fundraise for things like playgrounds, classroom technology and hot lunches, and to pay a growing array of fees for field trips, supplies and transportation. Teachers continue to subsidize school funding by paying large sums out-of-pocket for classroom supplies. Most concerning, class sizes are growing and classrooms host an increasing number of students with learning challenges or other special needs—with too few staff and resources made available to support them.

So what’s really going on here?

BC can afford to reinvest in public education now

To make sense of the funding crisis in BC schools, let’s start with the big picture. To what extent have we as a society prioritized public education in recent years? Is a major reinvestment in the system affordable? A look at the hard numbers is striking.

Arguably the best way to understand what we can afford to invest in public education is to look at BC’s overall economic pie to see how much of it we invest in the education system.

When we do that, we see a significant drop in the share of our total economic resources dedicated to public education. K–12 funding has fallen steadily from 3.3% of our province’s Gross Domestic Product in 2001 to a projected 2.5% in Budget 2016—which is a 25% decline.4

If we look only at the actual operating grants the province sends to school boards (excluding other expenses like new school construction and funding for the Ministry of Education itself), the drop is just as sharp, falling from 2.8% of GDP in 2001 to 1.9% in Budget 2016.5

These numbers are not small potatoes. A 0.9% decline in the share of GDP dedicated to education funding represents about $2 billion per year. (Yes, that’s ‘billion’ with a ‘b’.)

This is the additional amount we could invest in public education—in preparing our children for the future—if we wanted to simply dedicate the same proportion of our economic pie to K–12 education today as we did 15 years ago. While that level of funding increase might be beyond what’s necessary, it tells us what’s in the realm of the possible.

This decline in spending as a share of GDP also speaks to a legacy of ill-advised tax cuts in the early 2000s that have mainly benefited the wealthy and corporations, while eroding our capacity to fund needed services.

Public tax dollars, private schoolsEven as BC’s public education system faces a funding crunch, public tax dollars are flowing into private schools at a growing rate, including to elite prep schools that charge $20,000 per year in tuition. Funding for private schools has increased at more three times the rate of public schools over the past ten years, and is now projected to reach $358 million in the 2016/17 school year.6 The way that funding for private schools is calculated has also been concerning.7 Some special funding supplements are included in the public system to provide resources based on, for example, numbers of Indigenous students, English Language Learners, and adult learners (as well as to compensate for sudden enrolment declines). Private school funding levels are, in turn, set based on local public school funding. The upshot: many of these supplements are incorporated into the private school funding formula regardless of whether they actually have students in these categories. In addition to operating funding, private schools are also subsidized in other lesser known ways, including with property tax breaks on their facilities and, perhaps most galling, a “child care” tax break that parents at prep schools like Vancouver’s St. George’s School can claim for their children’s recess and lunch times.8 All this despite the fact that private schooling doesn’t actually yield better outcomes for students, according to a recent Statistics Canada report (instead, the apparent academic success of private school student is due to their socioeconomic backgrounds).9 A UBC study also found that students from public schools scored higher in first-year university classes than their private school counterparts.10 |

This year alone the provincial government declared a $730 million budget surplus, and stashed away another $300 million in a “prosperity fund” (misleadingly linked to LNG).11 It also sent over $310 million in public tax dollars to fund private schools (a practice opposed by three quarters of British Columbians, according to recent polling).

The idea that new education funding is unaffordable simply doesn’t wash. BC has the economic resources to reinvest in public education—it’s a matter of the government’s priorities.

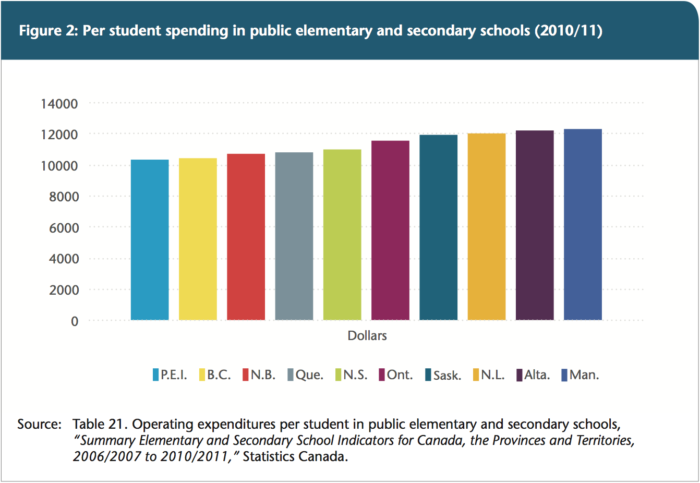

BC also has the ignominious distinction of having the second lowest education funding in the country, nearly $1,000 per student lower than the national average, according to the most recent data12 from Statistics Canada. This data is from 2010/11, but later school district level numbers—also from Statistics Canada—show that BC has continued to be a laggard in education spending compared to other Canadian provinces.13

Enrolment-adjusted school district expenditures increased from 2009 to 2013 by an average of 12.3% across Canada, while BC lagged behind at 5.6% (which after accounting for inflation is almost no increase at all).14

If there was any remaining doubt, even the BC Legislature’s own Select Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services acknowledges the funding shortfall in the public education system. Based on its province-wide consultations, the Committee reported that “current funding levels and assistance are inadequate, which is causing significant operational and program delivery problems in schools throughout BC” (emphasis added).

The Committee, which has a majority of MLAs from the governing party, specifically recommended increased funding, stating that “additional funding is necessary to ensure the provision of quality public education and to properly meet the increased cost that schools are currently facing.”

Yes, the province is responsible for the education funding crisis

So how can the government tell us that education funding is “at record levels” when the numbers—and even the government’s own Standing Committee—show it’s inadequate?

It’s technically true that the raw number of dollars going into education in BC has risen. The problem is that figure means very little on its own, as the costs of providing the same level of education have also risen. As much as government may like to brag about the dollar amounts of funding, ignoring the basic inflation rate and other cost pressures obscures the meaning of those numbers.

Besides inflation, the provincial government has fobbed off a whole array of additional downloaded costs to local school districts—costs the government largely controls, but doesn’t provide sufficient funding to cover. These include substantial increases in BC Hydro, Medical Services Plan (MSP), Employment Insurance (EI) and WorkSafeBC rates; the carbon tax; provincially mandated computer network upgrades; a proliferation of new technology in the classroom; as well as the cost of salary and benefit increases for teachers, support staff and administrators.15

One fact is clear: when these costs are increased without enough compensating dollars flowing into our schools, the system is left under enormous pressure.

According to an estimate released under Freedom of Information legislation, these kinds of cost pressures on school districts amounted to “a provincial cumulative total of [$192 million] for school years 2012/13 to 2014/15.”16

One fact is clear: when these costs are increased without enough compensating dollars flowing into our schools, the system is left under enormous pressure.

The discussion so far has focused on the operating side of the education budget, but funding available to BC schools’ capital and maintenance budgets has also not kept up with need. Many school districts face a growing bill of deferred maintenance as needed facility upkeep and repairs are postponed for lack of funds. For example, the province’s Annual Facility Grant for Vancouver schools has been flat for almost a decade, while costs of materials and labour have gone up. Meanwhile, a recent external audit found the Vancouver School District faces a whopping $700 million17 bill of deferred maintenance. As every homeowner knows, delaying repairs only makes the problems bigger and more expensive to deal with later.

When the province offers additional capital funding, it tends to come in the form of one-off announcements rather than consistent investments in the Annual Facility Grant. But predictable funding is what allows school districts to carry out effective long-term facilities planning. When lack of funding leads to indefinitely postponed repairs, the results can be disastrous. Think of lead contaminated water at Vancouver Island schools, asbestos exposure at a school in Abbotsford and delays in upgrading seismically unsound schools across the Lower Mainland.

Under the weight of downloaded costs and backlogs of deferred maintenance, school districts have been backed into a fiscal corner. As a result, districts around the province are forced to undertake substantial cuts—including school closures, increasing class sizes and scrapping music programs—that will be felt by students and will impact the quality of the learning environment in public schools. Most school boards have fallen in line to implement the cuts since they are required by provincial law to pass balanced budgets, which leaves them no other options. (A notable exception is the Vancouver School Board, which refused to approve additional cuts, risking being fired by the province as a result.)

The last-minute funding infusion: too little, too late

In the spring, the provincial government did make a series of education funding announcements (and re-announcements) billed as helping cash-strapped school districts. So one could be forgiven for thinking the problem is already being addressed. Unfortunately these last-minute funding infusions are a far cry from what’s actually needed.

The devil is in the details: government had actually mandated $54 million in administrative cuts over the past two years, and was now simply scaling back part of the original cut. There was no new money at all there.

Another $25 million was seemingly announced in the spring as a “reinvestment of administrative savings.” The devil is in the details: government had actually mandated $54 million in administrative cuts over the past two years, and was now simply scaling back part of the original cut. There was no new money at all there.

Incidentally,while “administrative” cuts might sound innocuous on the surface, the reality is that after years of underfunding, there was little actual administrative fat left to trim. As result, the so-called administrative cuts included cuts to school bus programs, custodial services, school supplies and library hours.

Declining enrolment is a red herring

The province frequently points to a decline in overall school enrolment in BC, arguing that funding levels are already adequate given the decline.

But this line of argument too deserves a much closer look. First of all, the funding crunch has hit school districts with declining and increasing enrolments alike, including the Surrey School District that is absolutely bursting with growth.

Where enrolments do decline, thousands of dollars are clawed back for each fewer student enrolled, but the operating costs of heating and keeping the lights on at a school with one fewer student stay largely the same, leaving a funding gap. For that reason, there have been growing calls to re-examine the per-student funding model in education, which has been in place since 2002.

In fact, an internal government memo from 2002 shows that Christy Clark (then Education Minister) recognized the shift to a per-student funding formula as a measure that would help deflect criticism of the government, which journalist Michael Smyth reported at the time.

According to excerpts from the memo, without Clark’s changes to the funding model, “the province will be seen as responsible for all costs. With overall flat funding and rising costs, this option would require the minister to decide annually which programs and services should be cut throughout the province. Responsibility for reductions will thus rest with the Ministry, not the local school board.”

Under the old funding model the government had to wear the blame for service cuts it imposed. Under the new per-student model cuts can be laid at the feet of school boards.

It’s also worth noting that today, when the government talks about certain schools’ failure to be 95% full, it actually considers dedicated art rooms and music rooms “empty.”18

By this logic, a school with seventeen 100% full classrooms, plus a dedicated computer lab, an art room and a music room to be shared by all students—in other words, an entirely full school—would be considered only 85% full and thus significantly “underutilized”.

In any case, while enrolments did decline in BC for a time, they’re headed right back up again. The government’s own data project an almost 40,000 student increase in enrolment by 2024.19

Underfunding schools compromises quality of education

In a way it’s quite strange to have to make a case for adequate investment in public education. We know how important it is to invest in young people today to build a solid economic and social foundation for our future. Moreover, in a province with persistent poverty, growing inequality and rising immigration, education can also be a great equalizer.

BC’s growing class sizes are a symptom of underfunding, and one with potential negative effects on student learning. The evidence is clear: investing resources to reduce class sizes substantially improves outcomes for students, and exerts an equalizing effect by helping disadvantaged students the most.20

We also know that kids with special needs and learning challenges deserve and benefit from getting classroom support. Yet the number of BC classes with four or more students with special learning needs has increased dramatically over the past ten years from around 9,500 to over 16,500—and the needed supports are stretched too thin. Prior to 2002 the ratio of students with special needs was limited to two per class in many school district contracts, but these limits were legislated away by the BC government.21

Perpetual funding crises also create a lack of stability and make it nearly impossible to engage in effective long-term planning at the local school district level. Responding to last-minute funding relief, the chair of the Quesnel School Board commented, “the timing of this is really bad… we’ve gone through the process of amalgamating schools, preparing kids, and staff layoffs.”

The Osoyoos School Board chair, facing similar circumstances, openly criticized the unpredictability of the current governance model that puts school boards in charge of balancing budgets, but makes them almost entirely dependent on provincial government funding levels in any given year. She noted, “we have advocated the ministry endlessly (for stable, consistent funding). We need something that we know is going to be there for the foreseeable future.”

Conclusion

Simply put, the rhetoric that education funding is “at record levels” doesn’t hold water. The provincial government has downloaded a whole range of increased costs onto school districts, even as provincial per-student funding has fallen far below the national average. Meanwhile, the share of BC’s economic pie dedicated to education funding has dropped sharply, giving lie to the notion that additional investments are “unaffordable.” To top it off, hundreds of millions of dollars in public funds are flowing each year to private schools.

The drop in public education spending—and overall public spending—as a share of our economy is not an accident. Rather, it’s a consequence of specific public policies like tax cuts that deliver the biggest bang to the richest British Columbians—in the process reducing the capacity to make critical investments in areas like education. In fact, households in BC’s top 1% now pay an extraordinary $41,000 less in tax per year than they did in 2001, and pay a lower overall tax rate than the vast majority of the population.

The truth is that we can invest substantially more in public education in BC, but we—or rather our government and policymakers—choose not to. As we’re beginning to see more clearly than ever, that choice has real consequences.

What’s the real story behind BC’s education funding crisis? Find out at https://t.co/nESMtOCnsb #bced #bcpoli pic.twitter.com/r8IGMfl7QA

— The CCPA–BC (@CCPA_BC) August 24, 2016

Notes

- See Families Against Education Cuts’ partial compilation of affected boards: “BC Ed in red” (April 10, 2016) at https:// facebc.wordpress.com/2016/04/10/bcedinred/

- For example, BC has seen significant hikes in Medical Services Plan premiums in recent years, as well as BC Hydro and ICBC rate increases, and tuition fee hikes. See also: Marc Lee, Iglika Ivanova, and Seth Klein, BC’s Regressive Tax Shift: A Decade of Diminishing Tax Fairness, 2000 to 2010 (Vancouver: CCPA-BC, 2011).

- Katie Hyslop, “For Vancouver parents, school fundraising ‘has become our lives’,” The Tyee. March 5, 2015.

- The additional funding announced in spring 2016 is too small to affect these numbers.

- This is not just an education story. There has been an even larger overall decline in provincial public spending as a share of BC’s economy over the past 15 years, falling from 21.7% of GDP in 2001 to a projected 18.6% this year.

- Based on government figures drawn from the 2005 and 2015 Ministry of Education Service Plan documents.

- Margaret White and Larry Kuehn, “Does independent school funding make a mockery of the public schools funding formula?” BC Federation of Teachers, April 2015. http://bctf.ca/uploadedFiles/Public/Publications/ResearchReports/RR2015-01(1).pdf

- Sandy Garossino, “Shameless: The hidden private school tax haven for the rich,” National Observer, June 22, 2015, http://www.nationalobserver.com/2016/06/22/opinion/shameless-hidden-private-school-tax-haven-rich

- CBC News, “Private school success due to better students, not better schools, StatsCan says,” March 31, 2015, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/private-school-success-due-to-better-students-not-better-schools-statscan-says-1.3016123

- CBC News, “Public school students better prepared for university,” April 23, 2012, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/public-school-students-better-prepared-for-university-1.1228791

- The prosperity fund money came from general revenue, not LNG-generated revenue – because there isn’t any.

- Table 21. Operating expenditures per student in public elementary and secondary schools, “Summary Elementary and Secondary School Indicators for Canada, the Provinces and Territories, 2006/2007 to 2010/2011,” Statistics Canada.

- For example, nominal dollar school board expenditures in BC increased at a far slower rate in BC than the Canadian average between 2011 and 2013, including after adjusting for enrolment changes. 2013 is the most recently Statistics Canada available data of this type. Calculations available on request. Based on CANSIM Table 478-0012 – School board expenditures, Statistics Canada; and Table 1, Number of students in public elementary and secondary schools, Canada, provinces and territories, “Elementary–Secondary Education Survey for Canada, the provinces and territories, 2013/2014,” The Daily, Statistics Canada, November, 19, 2015.

- Again, these figures include an adjustment for enrolment changes in the different provinces. Note, though, that the school district expenditure numbers are based on calendar years, while the enrolment numbers are based on a school years, so the adjustment for enrolment changes is inexact. Also, while accounting for inflation, these figures do not account for further and substantial cost pressures faced by school districts.

- In the case of the salaries, however, these have not even kept up with inflation. BC has among the lowest teacher salaries in the country compared to other provinces.

- The Ministry of Education document cites an analysis by the BC Association of School Business Officials.

- The audit estimate is referenced in a recent Vancouver School Board memo, “2016/2017 Annual Facilities Grant – Funding Allocation,” May 13, 2016, https://www.vsb.bc.ca/sites/default/files/16May18_op_commII_item1.pdf.

- This practice has been widely reported, including by Katie Hyslop, “Vancouver Vote for Seismic Funds Puts Schools on Chopping Block,” The Tyee, January 26, 2016.

- Projection Report for Public School Headcount Enrolments, BC Ministry of Education, March 2015, http://www2.gov. bc.ca/assets/gov/education/administration/resource-management/capital-planning/archive/1558a-2014.pdf

- The effectiveness of class-size reduction (2016). National Education Policy Center, Washington DC: http://nepc.colo-rado.edu/files/publications/Mathis%20RBOPM-9%20Class%20Size.pdf Does money matter in education? (2016). National Education Policy Center, Washington DC: http://nepc.colorado.edu/files/publications/Mathis%20 RBOPM-8%20Money%20Matters.pdf

- Seth Klein, “One year after the BC teachers’ strike, what’s happening for kids with special needs?,” Policy Note, September 5, 2015, https://www.policynote.ca/ one-year-after-the-bc-teachers-strike-whats-happening-for-kids-with-special-needs/