Fraser Institute, provincial government swing and miss again on education funding

My recent analysis of BC’s education funding crisis made some waves, travelling far and wide in the media and becoming one of our most-read papers of the year at CCPA-BC. Not surprisingly, it also drew critical responses that reflect some persistent myths about the funding crisis.

(You can hear my conversation [at 1:41:20] with CBC’s Stephen Quinn on education funding, and then check out the Minister of Education’s response.)

Myth #1: Education funding is higher than ever – trust us!

A week after my analysis was published, the Fraser Institute released its own report declaring that “contrary to what we hear from teachers, administrators and trustees” public education funding has seen “large increases” over the past decade. This is virtually the same line repeated by the provincial government (debunked in my original analysis), which continues to claim that BC’s education funding is at “record levels.”

When this government provides a few additional dollars to school districts with one hand, it grabs them right back again with the other.

To review: It is true that total dollars spent on public education in BC have increased. But that doesn’t tell us much. What the government and the Fraser Institute both consistently fail to account for is a host of new cost pressures that have been piled onto the education system.

Crucially, the provincial government itself controls many of these costs and has simply offloaded them onto local school districts. These include a doubling of MSP premiums since 2001, a 60% increase in BC Hydro rates since 2008, the carbon tax (plus an additional carbon levy on public sector organizations like schools), and mandated computer upgrades, among others.

Cost pressures on school districts amounted to more than $192 million by the 2014/15 school year, according to an estimate quoted in government documents released under Freedom of Information.

In short, when this government provides a few additional dollars to school districts with one hand, it grabs them right back again—and then some—with the other.

Even without accounting for these cost pressures, BC lags behind the rest of the country in public education funding – providing the second lowest per student funding in Canada, nearly $1000 below the national average, according to Statistics Canada data.

Strikingly, even the Fraser Institute’s report ultimately had to acknowledge this reality – though you won’t find it in their press release. But take a look at the section on interprovincial funding comparisons – it (correctly) concludes that BC provides the second lowest per student funding in Canada, and that its education spending growth has been slower than any other province in the country.

Myth #2: Declining funding as a share of GDP? Blame the accountants.

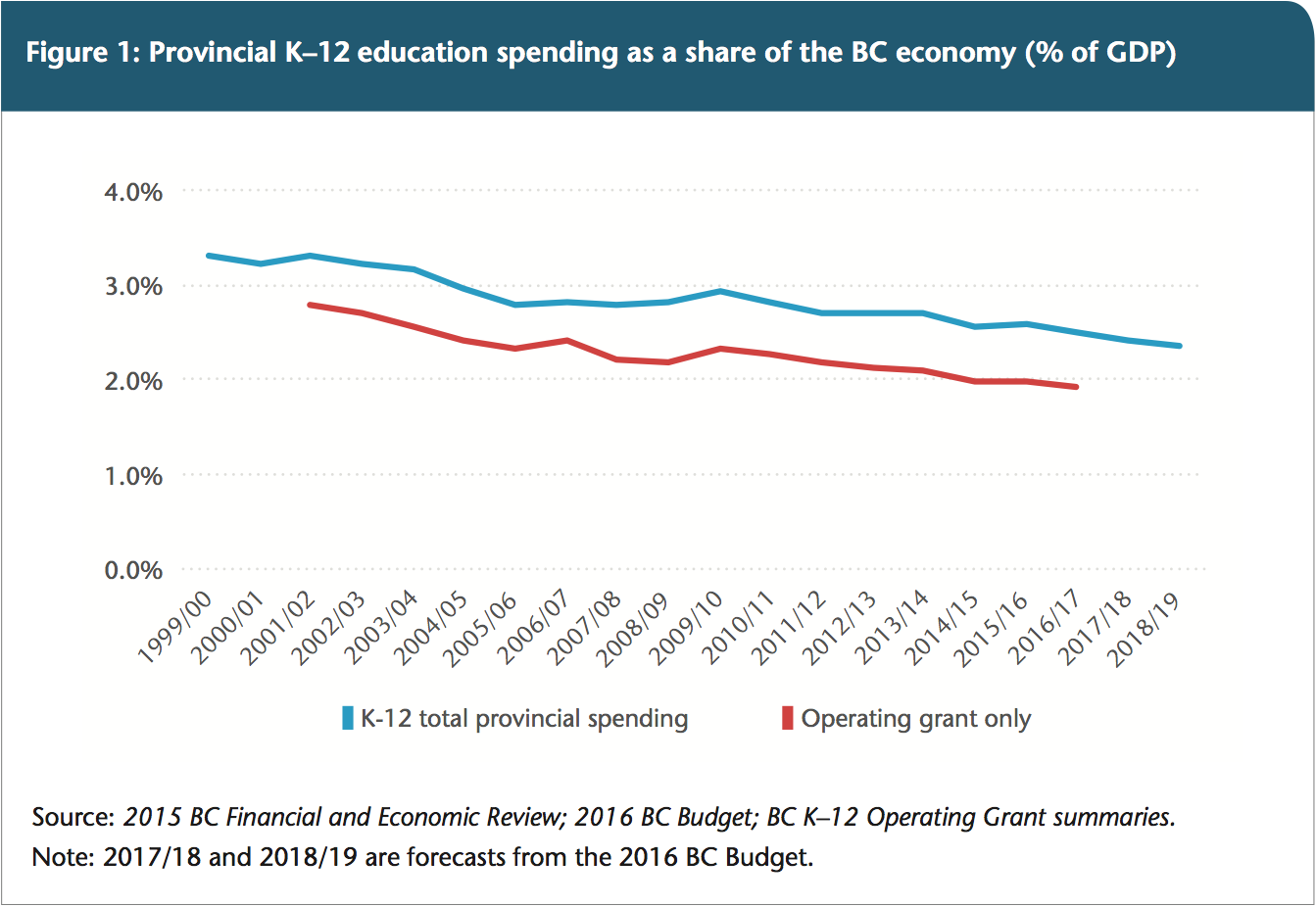

BC’s investment in public education has also declined sharply (by more than 25%) as a share of our total economic pie. This finding is important because it demolishes a frequent excuse: that we might like to reinvest in public education, but it’s not affordable.

The simple fact is that if we invested the same share of our GDP in public education as we did in 2001, we could invest an additional $2 billion in the system annually.

In reaction to my analysis, the Ministry of Education used some technical sleight-of-hand to dispute these findings. A Ministry spokesperson pointed to new accounting practices in its budget, including changes to the way capital costs and debt servicing were counted starting in 2009/2010. They tried to assert, as a result, that “the [CCPA] report’s GDP numbers are wrong.”

However, it’s actually the Ministry that has it wrong… again. This is important to set straight, because the government claim has been picked up by others, including the Vancouver Sun editorial board.

While it’s true that there were accounting changes in the budget, in my analysis I separated out the operating grant funding to school districts (see Figure 1), precisely because it excludes items like capital costs and debt servicing. These operating grant figures are unaffected by the accounting changes.1

Indeed, both the operating grant numbers and the overall education spending numbers show the same trend at work – a significant decline in education funding as a share of BC’s overall economic pie.2

Bottom line: the Ministry’s critique is simply incorrect.

Myth #3: We don’t need no (money for) education.

Columnist Lawrie McFarlane, in a piece bearing the headline, “Spending not a sign of education value”, argues that “the fundamental problem with this whole line of thought is that it fixates on inputs (money) rather than outputs (the quality of education).”

Now, in fairness, it’s certainly true that you can’t simply spend your way to success – in education or in any other endeavour. How money is spent is important, in addition to how much.

But Macfarlane ought to review the research on this issue.

Make no mistake: funding levels are critical. That’s confirmed by a new review of the academic research in this area, conducted by the University of Colorado’s National Education Policy Center. The review concludes that “money matters” and more specifically that “gains from investing in education are found in test scores, later earnings and graduation rates.”

The notion that a high-quality system can be chronically underfunded without consequence doesn’t hold water.

BC may have coasted for a time on the legacy of past investments in a strong public system, which attracted the best and brightest to teaching. But that system is being eroded before our eyes.

The notion that a high-quality system can be chronically underfunded without consequence doesn’t hold water. The research—and common sense—tell us otherwise.

A strong public education system is not just “nice to have” – it’s an essential, long-term investment that pays big social and economic dividends. Short-changing the system may yield some minor “saving” in the budget now, but only at a much larger cost to us all in the long run.

The truth is that we could invest substantially more in public education in BC, but we—or rather our government leaders—choose not to. That’s a choice that has real consequences.

A swing and a miss: @1alexhemingway debunks myths about K-12 education funding in BC https://t.co/E42ZkpRVxf #bced

— The CCPA–BC (@CCPA_BC) September 29, 2016

Notes

- For those who may want to see documents in which the accounting changes are reflected, you can refer to the annual “Ministry of Education Service Plan.” If you compare the 2008/09 and 2009/10 Service Plans, you can see that the line item “Debt Service and Amortization” (under the section “Resource Summary”) has been dropped and moved elsewhere starting in the 2009/10 document.

- The overall education spending numbers I used are, by every indication, also unaffected by the Ministry’s dubious critique. These figures are directly drawn from the government’s own published numbers, largely from the 2015 BC Financial and Economic Review – Table A2.7 (and from similar tables in the 2012 edition, as well as in Budget 2016). These government tables explicitly compare spending levels across years, and they are designed such that adjustments have been made for past accounting changes, in order to make sure the figures are comparable.

Topics: Children & youth, Education, Provincial budget & finance