From housing market to human right: A view from Metro Vancouver

I made the following submission to the Government of Canada’s consultation on National Housing Strategy’s human rights-based approach to housing, through which they are requesting “opinions and ideas about the key elements of a human rights-based approach to housing, the proposed approach to the new legislation, and new concepts to be explored.”

This submission outlines key reasons why the CCPA-BC would welcome a rights-based approach, and describes two central elements that would be needed: namely, a fiscal commitment to build affordable housing and to provide income supports.

Introduction

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the federal government’s National Housing Strategy and the proposed human rights-based approach to housing. I live and work in Vancouver, BC where the housing crisis is arguably the most acute. My comments will thus reflect a Vancouver and BC perspective, and are based on research I have done on the housing system as an economist for the BC Office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

For a growing number of Canadians, particularly those in large cities like Metro Vancouver, the housing market is broken. At its core, this is a problem of financialization—the treatment by many actors of housing primarily as an investment, rather than a place to live. The current discussion of housing as a human right should challenge that proposition. In particular, I would like to comment on two core aspects of the National Housing Strategy, both of which need to be shored up: a major build-out of non-market housing; and a more coherent housing and income support in the form of the Canada Housing Benefit.

The housing market is failing many households

In Metro Vancouver the failure of the housing market is evident in the phenomenal cost of purchasing residential real estate, but also a serious crisis in the rental market, inadequate housing for the most needy, and persistent homelessness. Based on the 2016 Census, Metro Vancouver’s housing market breaks down as one-quarter owners without mortgages, 38% owners with mortgages, and 36% renters (more than half were renters in the City of Vancouver). Some 14% of renter households rent specifically within the social housing realm, the development of which is central to a human rights-based approach.

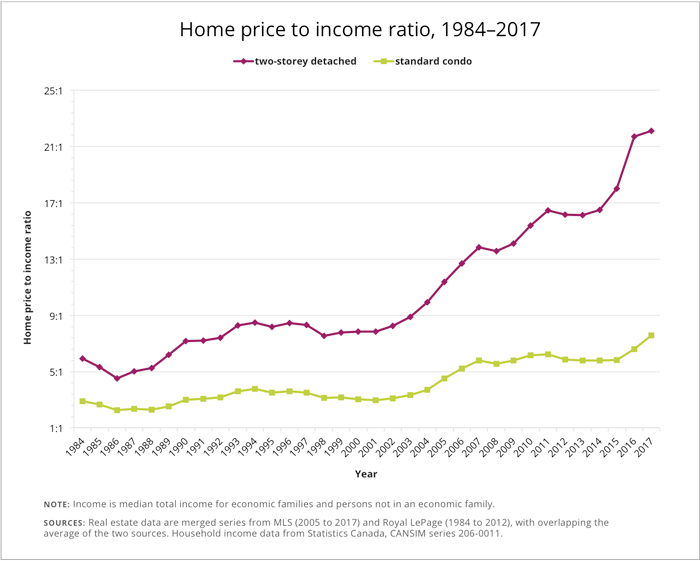

For housing ownership, home prices have become decoupled from the incomes of ordinary, working households. The figure below shows that between 1984 and 2000 the price of a standard condo in Metro Vancouver was fairly stable at three times median income, while a two-storey detached house was seven times median income. Price escalation since 2001 is striking, with a standard condo hitting 7.6 times median income, and a two-storey detached house a jaw-dropping 22 times median income, in 2017.

This home price inflation has created spectacular windfall capital gains for many homeowners, although in many cases these are unrealized as they continue to live at the same home. Those who purchased in recent years may be financially vulnerable to an increase in interest rates or a slowdown in the economy resulting in job loss. Renters face a bigger and bigger wall separating them from the dream of owning their own home. This soaring of home prices is perhaps the single largest driver of inequality in recent years and is undermining the economic security of low- to modest-income households.

Households in the rental market are stuck not just in terms of being unable to shift into home ownership but also into different rental housing. Vacancy rates for rental housing in Metro Vancouver have been below 1% for several years, and this has pushed up rents dramatically. The vast majority of new rental stock is not purpose-built rental but rented condos and secondary suites. CMHC data show a premium for the latter secondary market units, ranging from 13% and 15% for bachelors and one-bedrooms to 20% for two-bedrooms and 50% for three or more bedrooms.1

Some of this differential reflects new units in better condition, but another key aspect is the ability of landlords to end-run BC’s rent controls. Tenants in the secondary market are at greater vulnerability of being displaced due to renovations (“renovictions”) or re-occupancy by the owner. Households forced to change their rental accommodation are thus likely to pay much more in rent. These shifts take place on the margin and are not as statistically visible when averaged across all renters. For example, CMHC reports that the average rent for vacant units is 11% higher than for occupied units “suggesting that market rents currently faced by prospective tenants are seeing strong upward pressure due to the low number of vacancies in the market.”2

In the context of a very tight rental market, concerns have arisen that Airbnb and similar short-term rental services are diverting some of the longer-term rental stock. This is a relatively new and lucrative income stream for landlords that exacerbates the affordability challenge. The City of Vancouver has moved to regulate this area, restricting listings for “entire home/apartment” (that is not a principal residence), the category most likely to displace long-term rentals, while allowing private or shared rooms within the principal residence.3

Soaring home prices is perhaps the single largest driver of inequality in recent years and is undermining the economic security of low- to modest-income households.

All of this has occurred as Metro Vancouver has experienced a long housing construction boom. More than a decade ago the promise was that more supply would make housing more affordable. But developers have too often been building luxury supply as investment properties for people who do not live or work in the region, rather than housing that meets the needs of those who do. Housing demand has been bolstered by external capital flows from outside Canada and from other parts of Canada, but also by a prolonged period of low interest rates, and the transmission of housing gains from parents to children (“the bank of Mom and Dad”).

The biggest affordability challenge in Metro Vancouver is clearly for renters, which highlights the need for greatly expanding the city’s dedicated rental housing stock and in particular various forms of social and cooperative housing. The most recent Census shows that more than two in five (43%) pay more than 30% of income for their housing, and for those in subsidized rental housing (who are likely to have lower incomes), the figure rises to 57%.4 Across all renters, 22% are paying more than half their income in shelter costs. Moreover, certain household types experience a greater incidence of core housing need than the average: lone seniors and single-parent families, Indigenous households, and recent immigrants.

Housing as a human right

Canada is a signatory to United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The right to housing is subsumed under the “right to an adequate standard of living” in Article 25:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

This is echoed in Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. While Canada is a signatory to both agreements, action by governments to realize their obligations under the right to housing has largely been absent.

Two central elements needed for a human rights-based approach in the National Housing Strategy (NHS) are the development of non-market housing and income supports to ensure adequate housing. In both areas the federal government could improve upon the framework of the NHS to better secure affordable housing for low- to moderate-income households.

Significantly expand the construction of non-market housing

In other countries, public or non-market housing has long been part of the solution. Across OECD countries, Canada’s social housing rate of 4% is much less than comparable advanced countries like the Netherlands (34%), Austria (26%), Denmark (22%), France (19%) or the UK (18%).5 In Singapore, some 82% of residents live in 900,000 apartments built by the city-state’s Housing Development Board.6 In the city of Vienna, Austria, almost half of the total housing stock is social housing, and the city acts as a developer.7

Canada can also look to its own history of building dedicated affordable housing in the post-war years. The federal government was central in putting funds on the table for provincial partnerships, often with a ⅔ federal, ⅓ provincial split. Another key player was non-profit community groups, such as church groups and cooperatives, who came together to apply for funds, incorporating land and other equity from fundraising as part of their applications. Consequently, between the early 1970s and the early 1990s, BC used to bring on stream approximately 2,000 units of new social or co-op housing each year. This legacy of social and cooperative housing is more than 50,000 units in Metro Vancouver.8

Developers have too often been building luxury supply as investment properties for people who do not live or work in the region, rather than housing that meets the needs of those who do.

Planned federal commitments in the NHS to build dedicated new affordable housing are limited. While efforts to preserve existing social housing through renewal of their operating agreements is notable and most welcome, a dedicated multi-decade pipeline of new affordable housing construction is needed. The headline commitment of 100,000 units sounds large, but it is nation-wide, over a period of ten years, and assumes provincial contributions. The specific federal commitment of 60,000 units over ten years to be provided through a new National Housing Co-Investment Fund works out (based on population share) to an average of about 790 new units in BC per year, about half of which would be in Metro Vancouver. That is far less than what is needed to meaningfully address affordability.

The broad range of needs includes specific challenges—housing for the homeless, supportive housing, seniors’ housing and assisted living, and immigrant and refugee settlement—as well as more broad-based rental housing. With a growing population increasing the demand for affordable rental accommodation, I estimate Metro Vancouver needs between 5,000 and 10,000 new units per year.9

Building this amount of non-market housing requires substantial upfront capital costs. At approximately $250,000 per unit, this would mean an investment in BC of $1.25 to $2.5 billion per year for 5–10,000 units respectively. However, those costs would be paid back through the flow of rental income over the lifespan of the buildings. Costs can be driven down if land is contributed through a local government or non-governmental partner. Cutting out developer profit margins (generally thought to represent 10–20% or more of the sale price of new housing) is another means of reducing the upfront costs of affordable housing.

The 2018 BC Budget makes some major strides in this area, with a commitment to 33,700 units over 10 years. The National Housing Strategy should aim to deliver on a similar scale, with a focus on developing new rental social and co-op housing.

Funding for this build-out should come from taxing some of the windfall gains received by home owners due to higher property values. We have urged shifts to progressive property taxation and taxes on speculative activities at the provincial level (adopted in BC Budget 2018). Federally, taxing capital gains on principal residences (with a lifetime exemption up to $500,000) would be an ideal source of funding a more significant build out of affordable non-market housing.

The Canada Housing Benefit

Given the prevailing distribution of income and rental costs, income supports are required for low-income households. The proposed $2,500 per year Canada Housing Benefit (CHB) could greatly assist in this regard, and it would be a welcome addition to income supports at the federal level (i.e. for seniors, children and unemployed workers). Accelerating the benefit so that it launches before its intended 2020 start date would be advisable.

Given the prevailing distribution of income and rental costs, income supports are required for low-income households.

That said, many details are missing around the form of the CHB. A concern is that the CHB may simply enable landlords to raise rents, particularly in a tight rental market like Metro Vancouver’s. An innovative policy response to this situation is Manitoba’s Rent Assist program, which began in 2015. By design, qualifying renters (below a specified income threshold or on social assistance) in the private market do not pay more than 28% of their gross income in rent (based on 75% of the median market rent), with the rental assistance subsidy bridging the gap between that amount and actual rent.10 This program raised housing benefits for people on social assistance without the increase going to landlords in increased rent; it is also an income-tested benefit for those not on social assistance, so there is no loss of benefits when moving off of social assistance. The benefit is based on income not rent, so it is portable should the person or family move.

How the federal contribution links to provincial efforts is also in need of clarification. Federal policy should ensure that the CHB is not clawed back in provinces like BC that have their own rental assistance programs. Indeed, with provincial matching contributions the combined benefit would provide significant gains for households at the low end of the income spectrum where the most assistance is needed. The federal contribution could also provide incentives for provincial rental assistance to be more broadly available—BC’s rental assistance is only available to families not on social assistance and low-income seniors (approximately 30,000 households).

These efforts to increase income supports for housing may lead to commentary that governments should not subsidize renters. However, if anything it is homeowners who are currently subsidized by governments, not renters. Housing ownership is very favourably treated in terms of incentives and the tax treatment of property—such as the fact that sales of principal residences are not subject to capital gains taxes, meaning windfall gains from rising housing prices go untaxed—which favour owners. A study of these comparative subsidies and tax expenditures in the province of Ontario found that 94% of the fiscal benefit of housing policy goes to homeowners (mostly, non-taxation of income related to owner-occupied housing, plus home renovation tax credits), rather than to renters.11

**

In summary, there is much promise from the National Housing Strategy, especially when combined with provincial and municipal efforts. Developing a rights-based approach to housing inevitably means a more determined fiscal commitment to build affordable housing and to provide income supports. In a wealthy country like Canada, making housing a human right would lead to a profound increase in economic security for low- to moderate-income households.

Notes

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2017), Rental Market Report: Vancouver CMA.

- Ibid.

- City of Vancouver, Is your home eligible to have a short-term rental?

- Marc Lee (2017, November 27), Rising housing costs in Vancouver: New evidence from the Census: Policy Note.

- OECD, Affordable Housing Database, PH 4.2: Social rental dwellings stock.

- Singapore Housing Development Board (2013), Public Housing in Singapore: Residents’ Profile, Housing Satisfaction and Preferences.

- Kathleen Scanlon, Christine Whitehead and Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia (2007), Social Housing in Europe: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Metro Vancouver, Housing Data Book 2018.

- Marc Lee (2016), Getting Serious About Affordable Housing: Towards a Plan for Metro Vancouver: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- Josh Brandon, Jesse Hajer and Michael Mendelson (2017, October), What does an actual housing allowance look like? Manitoba’s Rent Assist program: Caledon Institute.

- F Clayton (2010, August 30), Government Subsidies to Homeowners versus Renters in Ontario and Canada: Prepared for Federation of Rental-Housing Providers of Ontario and Canadian Federation of Apartment Associations.

Topics: Housing & homelessness, Poverty, inequality & welfare